These Odd Bony Structures Were Hiding Beneath the Skin of Far More Lizards Than Thought, Researchers Find

Called osteoderms, the chain mail-like plates may have helped some species adapt to Australia’s harsh environment

Roughly 20 million years ago, monitor lizards, also known as goannas, appeared in Australia. These reptiles not only adapted to the region’s harsh environment—they thrived in it. And that success could be partially thanks to chain mail-like bony structures in their skin called osteoderms.

An international team of researchers has conducted the first large-scale global study of osteoderms in lizards and snakes. By investigating previous scientific literature on the topic and analyzing specimens from museum collections, they discovered osteoderms on countless species—including several goannas—that were previously thought to lack them. In all, they revealed that nearly half of all lizard genera have osteoderms, which is 85 percent more than scientists previously estimated, according to a statement from Museums Victoria.

The team published their findings on Monday in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.

Key concept: What are osteoderms?

Osteoderms, literally meaning “bone skin,” are bony structures found in the skin that are detached from an animal’s main skeleton. They’ve evolved separately in species ranging from reptiles to amphibians and a few mammals.

Millions of years ago, bony osteoderms evolved into the famous armored plates and spines of stegosaurs and ankylosaurs, as Imma Perfetto reports for Cosmos. Today, they’re present in animals such as crocodiles and armadillos, but researchers have struggled to pin down their specific purpose.

Physical protection seems like osteoderms’ most obvious function, but scientists have also suggested mobility, heat regulation and even calcium storage during reproduction.

In “lizards and their relatives, osteoderms may be completely absent, present only on the head or dorsum, or present all over the body in one of several arrangements,” a different team wrote in a 2021 study. “This diversity makes lizards an excellent focal group in which to study osteoderm structure, function, development and evolution.”

Even when osteoderms are present in an animal, they’re hidden within skin tissue. That means that identifying them in museum specimens has typically involved significant damage to the remains, study lead author Roy Ebel, an evolutionary biologist at the Museums Victoria Research Institute, writes in the Conversation.

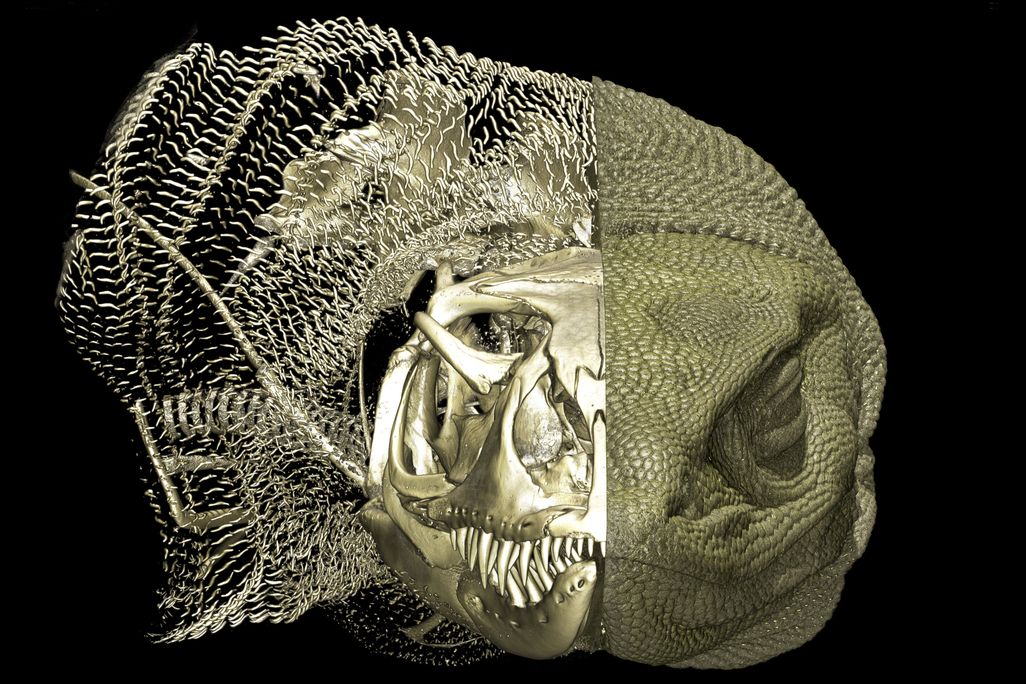

As such, the team “turned to micro-computed tomography (micro-CT), an imaging technique similar to a medical CT scan, but with much higher resolution,” Ebel adds. “This allowed us to study even the tiniest anatomical structures while keeping our specimens intact.”

The group took 1,339 micro-CT scans and sifted through 584 mentions in scientific studies. They generated 3D models of the specimens and used a technique called radiodensity heatmapping to highlight bone structures in their bodies.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/36/e3/36e35cdc-5a54-4847-98f8-663c41940a65/scientists-uncover-hid-1.jpg)

Their approach revealed the previously undocumented presence of osteoderms in 29 Australo-Papuan goanna species. Scientists have been analyzing these lizards for over two centuries, and it was thought that only a few of them—such as the Komodo dragon—had osteoderms. Uncovering these structures in more goannas was thus their “most astonishing” find, Ebel writes in the Conversation.

The study “reshapes what we thought we knew about reptile evolution,” Jane Melville, senior curator of terrestrial vertebrates at the Museums Victoria Research Institute, who is not an author of the study, says in the statement. “It suggests that these skin bones may have evolved in response to environmental pressures as lizards adapted to Australia’s challenging landscapes.”

With more research, this data set might reveal even more discoveries about lizard skin and how it has helped the reptiles survive for millions of years.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Margherita_Bassi.png)