How Underwater Archaeology Brings Secrets to the Surface, From Lost Shipwrecks to Submerged Cities

An immersive new exhibition at the Intrepid Museum in New York City spotlights the science and technology behind the discipline

Key takeaways: What to know about underwater archaeology

- Underwater archaeology, or the study of submerged sites and artifacts, isn’t limited to shipwrecks and downed aircraft.

- Experts in the field also survey underwater cave systems filled with the remains of now-extinct animals and sunken cities like Pavlopetri in Greece, among other sites.

In July 1860, the Clotilda—the last known slave ship to arrive in the United States—landed in Mobile, Alabama. The wooden vessel’s cargo hold measured around 500 square feet, about the size of a studio apartment, yet it carried 110 enslaved people from the West African city of Ouidah, located in present-day Benin. Ranging in age from 5 to 23, these men, women and children endured a grueling six-week journey across the Atlantic Ocean in cramped, inhumane conditions.

The United States had banned the importation of enslaved people more than five decades earlier, in 1808. But an Alabama businessman hoping to win a bet reportedly hired the Clotilda’s captain, William Foster, to prove he could sneak a slave ship into the country without getting caught. After he’d offloaded his captives, Foster set the Clotilda on fire and sank it to destroy evidence of the illegal voyage.

Researchers aided by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture found the Clotilda’s wreck in 2019. Working in near-zero visibility and strong currents, the team identified key features, including burned wooden planks and iron fasteners, that matched historical descriptions of the ship. Now, six years later, a 3D-printed model of the Clotilda is featured alongside the stories of those it trafficked in a new exhibition at the Intrepid Museum in New York City.

Titled “Mysteries From the Deep: Exploring Underwater Archaeology,” the immersive show draws on interactive experiences, 3D reconstructions, excavated artifacts and personal accounts from experts to examine “sunken aircraft, shipwrecks, submerged cities and lost landscapes,” per a statement. Its goal is to spotlight how underwater archaeology—the study of human history through the recovery and analysis of submerged sites and artifacts—is a powerful tool for preserving cultural heritage, enabling scholars to unravel mysteries of the past.

Jeremy Ellis, a sixth-generation descendant of two Clotilda survivors, Pollee and Rose Allen, was involved in the exhibition’s curation process and appears in two videos featured in it. “I was able to proofread the language that you see in the exhibit around Clotilda,” he says. Through this work, Ellis was able to “share a little bit about Clotilda, my ancestors specifically, and how important this archaeological work is for the community and the descendant community.”

“Mysteries From the Deep” is a collaboration between the Intrepid Museum, which is housed on the World War II aircraft carrier of the same name, and the traveling exhibition company Flying Fish. The Manhattan museum explores the intersection of history and innovation through its collection of aircraft, submarines and space artifacts, including the Enterprise space shuttle and the Concorde supersonic passenger plane.

Behind the scenes at the “Mysteries From the Deep” exhibition

The vision for “Mysteries From the Deep” originated before the Covid-19 pandemic, when the Intrepid Museum first approached Flying Fish about showcasing its underwater artifacts, says Jay Brown, the exhibition company’s principal and managing director. The project got shelved until 2023, when its focus changed. “We’ve broadened the scope to be more encompassing of the science and technology behind underwater archaeology rather than just focusing on the artifacts,” Brown says.

Stephanie Hanson, an exhibition developer for Flying Fish, says that each section of the show was designed to mimic the real stages of an archaeological dive, from discovery to conservation. The team’s aim was to highlight the people behind underwater archaeological discoveries. “These experts do amazing work, and they’re so passionate,” Hanson says. “I hope that visitors get inspired from that.”

In the exhibition, museumgoers encounter displays about World War II plane wrecks; submerged Indigenous landscapes; ancient cities like Pavlopetri in Greece; and, of course, the tools needed to explore underwater, such as remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and diving equipment.

The curators have emphasized interactivity throughout, offering touchable displays, like replica skulls of extinct animals recovered from submerged caves, and even a personality test to determine what kind of underwater archaeologist you might be. Artifacts such as a dive helmet and boots, wood samples collected from wreck sites, and a cradle built to transport a giant ground sloth’s pelvis to the surface are on loan from institutions including the U.S. Naval Undersea Museum; the University of Michigan’s Museum of Anthropological Archaeology; and the University of California, San Diego.

The exhibition is bilingual, with text written in both English and Spanish, and offers multiple entry points for different kinds of learners. One screen-based game allows visitors to explore a rendering of what the Alpena-Amberley Ridge, a dry land corridor in Lake Huron, might have looked like when it rose above the water’s surface about 9,000 years ago. Other options include tactile objects, such as 3D models of ceramic jars from historic shipwrecks, as well as displays of diving gear like rebreathers and ROVs. “We’re just trying to provide a different way of engaging with the content that feels like you can learn something and kind of play,” Hanson says.

One of the highlights of the exhibition is an interactive touchscreen experience that simulates diving into Hoyo Negro, a submerged cave system in Quintana Roo, Mexico. Using 3D-modeling technology, the game places visitors in the role of an underwater archaeologist tasked with exploring the cave and discovering the bones of extinct animals—all before oxygen runs out.

Among the most notable discoveries made at Hoyo Negro is Naia, the skeleton of a teenage girl who fell into a pit in the cave system and died some 12,000 years ago. Naia’s DNA has provided critical clues about the origins of the first Americans. She is briefly mentioned in the exhibition; her inclusion, and that of other people whose remains have been found in submerged sites, was treated with sensitivity, Hanson says. She adds, “We chose not to really feature her that much because we just feel like we should have dedicated more space if we were to really talk about her.”

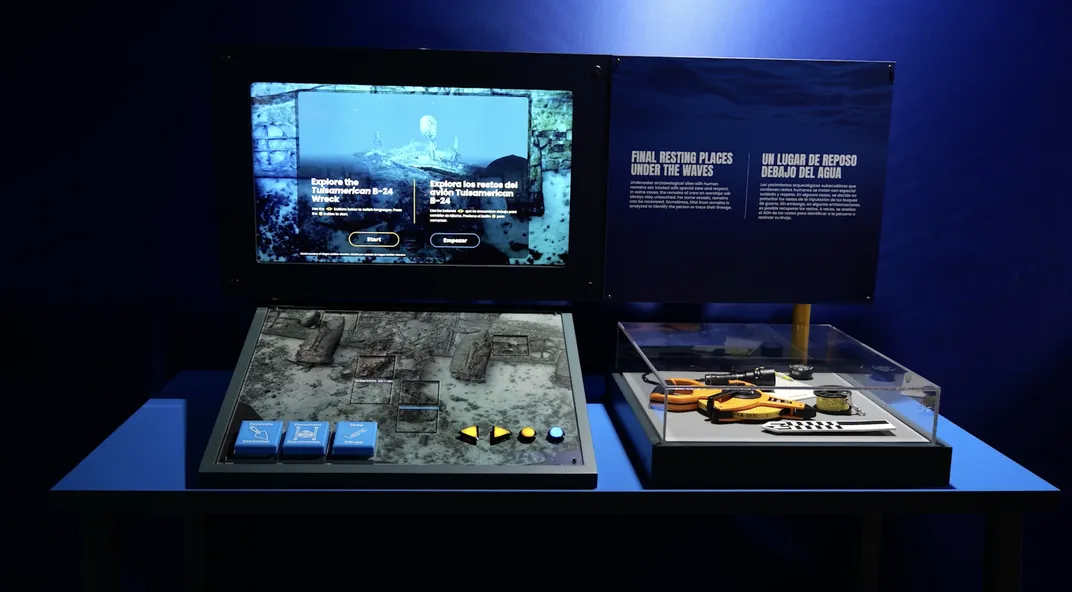

In addition to simulating excavations, “Mysteries From the Deep” asks visitors to try their hand at identifying objects recovered from archaeological sites. “Conservation has to occur with every single item that’s brought out from underwater because they’re all affected by saltwater and their time spent underwater,” says guest curator Megan Lickliter-Mundon, who brought firsthand expertise to the exhibition from her work on wartime wrecks, including the Tulsamerican, the last B-24 bomber produced in Tulsa, Oklahoma, during World War II. In the show, a screen-based interactive station allows visitors to simulate the process of excavating and documenting different parts of the aircraft’s wreck.

The Tulsamerican went down over the Adriatic Sea in December 1944 while returning home from a bombing mission; its wreck was identified in 2010, near the Croatian island of Vis. In 2015, Lickliter-Mundon and her colleagues embarked on a research project that led to the recovery of the remains of Army Air Forces First Lieutenant Eugene P. Ford, a member of the Tulsamerican’s crew.

The wreck lies at a depth of approximately 130 feet, so the survey team created a 3D model to visualize the site before diving down to it. “Your normal recreational scuba diving would only go to 100 feet,” Lickliter-Mundon says. “If you push the limits of normal recreational scuba diving, maybe 150 feet. But the pressures on your body are so great that the deeper that you go, the shorter [the] amount of time that you can spend down there.”

The role of community-led archaeology

One of the exhibition’s most powerful elements is its collaboration with Diving With a Purpose (DWP), a nonprofit dedicated to training Black divers in maritime archaeology, which falls under the umbrella of underwater archaeology but focuses more specifically on evidence like shipwrecks and port structures, which hold insights on how humans have interacted with bodies of water throughout history. Jay Haigler, one of DWP’s founding board members and the organization’s lead diving instructor, is recognized in the show for his role in the search for the Clotilda.

Haigler believes underwater archaeology is about more than technical recovery. “It’s about the awareness of submerged cultural resources,” he says. “And that’s hard work and can be very expensive, but the many stories that I’ve told from the depths of the sea and the ocean are amazing.”

DWP has trained hundreds of divers in collaboration with archaeologists, researchers and museums around the world. The group’s work on the Clotilda has not only helped verify the wreck’s identity but also given descendants like Ellis a direct connection to their history. Through DWP, Ellis became a certified scuba diver himself. “I would like to be a descendant that actually dives the ship that his ancestors came in,” he says. “I think that that would be a very powerful story.”

Visitors to the exhibition can see footage and photographs from DWP missions, hear firsthand accounts from divers, and explore how the organization brings submerged African diasporic history to light. As Haigler says, “When you’re able to … speak with direct descendants, you can no longer say it was a long time ago.”

Why underwater archaeology matters now

The field of underwater archaeology has become more visible in recent years, thanks in part to advances in technology and a broader push to reckon with the legacies of colonialism, racism and slavery.

Beneath the ocean’s surface, sunken slave ships like the Clotilda offer tangible evidence of these global systems. Though not featured in the exhibition, the wreck of the São José-Paquete de Africa, which sank off the coast of South Africa in 1794, has also been crucial to understanding the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Similarly, the remains of warships from World War II and colonial naval conflicts help document shifting power dynamics and unresolved mysteries. As for submerged cities, they allow archaeologists and communities alike to learn about histories and cultures that have long been hidden, forgotten or erased.

Underwater archaeology is legacy work, Haigler says. The Clotilda, for instance, is not just a story of slavery but, more importantly, one of triumph. In 1866, the ship’s newly emancipated survivors established a community called Africatown just north of downtown Mobile. Unable to return to their homeland, they built a new home—one where they spoke Yoruba and selected their own leaders. Today, their descendants continue sharing their ancestors’ history.

“This is [a] story about resilience of the human spirit,” of people who survived slavery, won their freedom and founded Africatown, says Haigler. “Hundreds of years later, it still exists.”

As Susan Marenoff-Zausner, president of the Intrepid Museum, explains, “‘Mysteries From the Deep’ is about more than just artifacts. It’s about people, divers, archaeologists, families, ancestors and communities, all working to preserve legacies and illuminate history from the depths.”

“Mysteries From the Deep: Exploring Underwater Archaeology” is on view at the Intrepid Museum in New York City through January 11, 2026.