A Smithsonian magazine special report

How a Relentless, 484-Mile March From Virginia to Massachusetts Fueled the Legend of the Dashing Frontier Rifleman

In the early months of the American Revolution, Daniel Morgan and his soldiers raced north to join the Continental Army during the so-called Beeline March

When Daniel Morgan’s company of 96 riflemen left Winchester, Virginia, on July 15, 1775, they were bound for Cambridge, Massachusetts, and possible battle with the British. Along with nine other militia companies from Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania, Morgan’s men heeded a call for military support from the Continental Congress and headed north to fight in the American Revolution. Their trip would later become known as the Beeline March, a relentless, nearly 500-mile trek in service of the patriot cause.

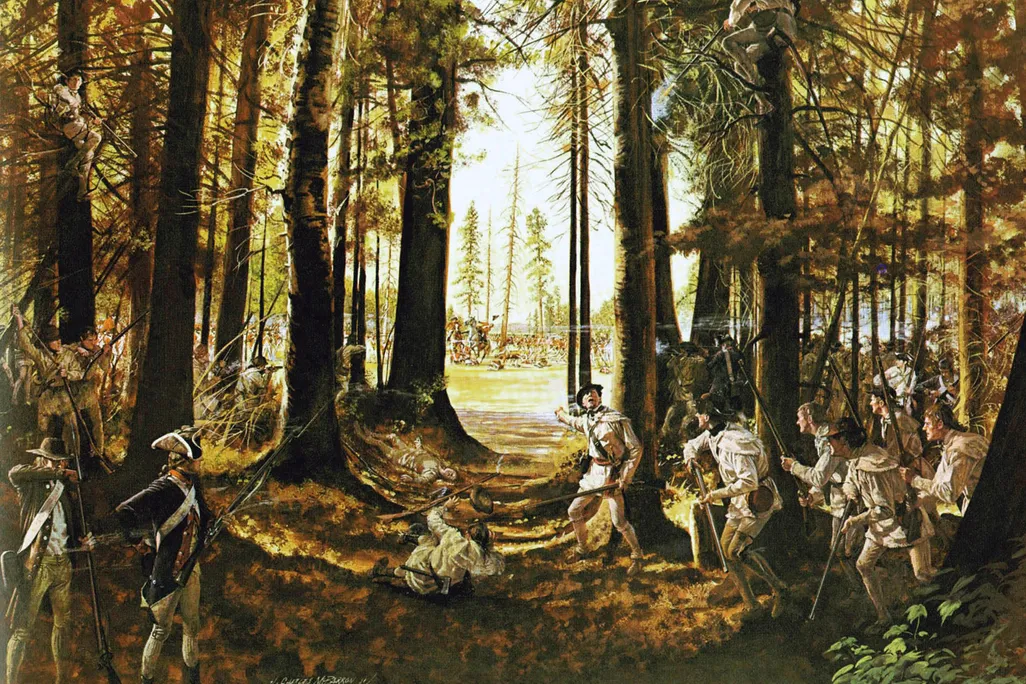

A key figure of the Revolutionary War, Morgan was a skilled military strategist with a mysterious past and a rough persona. As a young man, he’d been “addicted to drinking and gaming”—habits that entangled him in “numberless broils and difficulties,” wrote biographer James Graham in 1856.

Morgan worked as a teamster during the French and Indian War, hauling supplies for the British. (His nickname was the “Old Wagoner.”) Tall and broad, he cut a vivid figure, even more so after he attracted the ire of a British officer and was sentenced to 500 lashes. When Morgan later told stories about his punishment, says historian Albert Louis Zambone, author of Daniel Morgan: A Revolutionary Life, listeners would understand from his insistence that he only received 499 lashes that he stayed fiercely conscious the whole time, counting each strike of the whip. After the flogging, Morgan officially enlisted in the British Army as a ranger; he was shot in action in 1757 but escaped with his life.

When the American Revolution began in April 1775, Morgan—by then a married yeoman farmer—sided with the patriots. As soon as he received word to come to Massachusetts at the head of a rifle company, “Morgan, burning with ardor, lost no time in delay,” according to Graham. “In less than ten days after the receipt of his commission, he raised a company of 96 young, hardy woodsmen, full of spirit and enthusiasm, and practiced marksmen with the rifle.” Though the companies were only supposed to number 68 privates each, enthusiastic recruits brought the final total up. Morgan’s riflemen, along with those in the other companies requested by Congress, made a splash among colonists who had never seen grizzled soldiers from the American frontier before.

When the riflemen camped in towns, locals turned out to see them. They wore hunting shirts, which were “very democratic, because they don’t have any kind of stripes or insignia on them,” says historian Robert G. Parkinson, author of Heart of American Darkness: Bewilderment and Horror on the Early Frontier. “They take their shirts off, and they have scars all over their body—they’ve been shot before. It’s this idea that bullets can’t kill them. They sleep outside, and all they need is a little bit of fresh air and a little bit of bread, and they can live forever. It’s turning them into demigods.”

Zambone describes Morgan’s pace during the Beeline March as “remarkable,” adding, “He moves fast even by modern infantry standards,” about 23 miles a day for 21 days, over 484 miles. Morgan’s speed partially stemmed from his experience as a teamster. He was an expert at logistics and knew how to load baggage efficiently. “He’s determined he is going to beat everyone else to Cambridge,” Zambone says. “This is really what creates the myth of the American rifleman, within weeks.”

Newspaper coverage of other Beeline militiamen—for example, a troop of Marylanders—contributed to that legend, says Parkinson. The marchers’ weapon of choice also fueled their dashing reputation. As historian John W. Wright wrote in 1924, American gunsmiths made great improvements to the rifle following its introduction to the Thirteen Colonies around 1700, transforming it into “a long, slender, small-bore gun … a weapon of accuracy.”

In Zambone’s view, the rifle “is one of the great American folk arts.” He says, “It combines a German technology and improves and changes it for the Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia frontier. American wood and American English metalworking traditions create this absolutely unique piece of technology and art. It’s highly idiosyncratic.”

In comparison, the smooth-bored weapon that the British Army used “was of low velocity, high trajectory, strong recoil, limited accurate range and slow fire,” according to Wright. The American rifle’s superiority made the British “much more worried about Americans killing their officers because they can reach them much better,” Parkinson says.

The American rifle—and the militiamen’s skill with it—gave the patriots faith at the outset of the Revolution. The weapon was “part of the miraculous thinking [that characterizes] the beginning of every war,” says Zambone. “It’s this special technology of special people who will be able to win the war just by shooting a few rounds.”

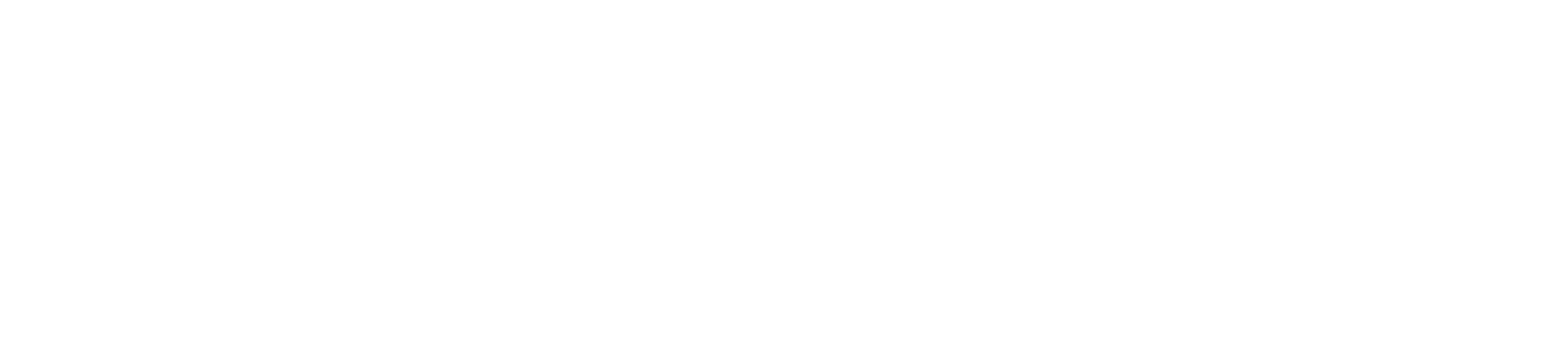

A few days into the journey, local militiamen escorted Morgan’s company through the town of Frederick, Maryland. The soldiers, one local man wrote, were “breathing nothing but a desire to join the American Army and to engage the enemies of America’s liberty.” In August, a different rifle company in Frederick performed what Parkinson calls a William Tell act, after the Swiss folk hero who supposedly shot an apple off his son’s head. During the showcase, riflemen shot at a small target while lying on their sides or on their backs. Two brothers took turns, each holding a board over his head while the other fired at it.

A 22-year-old rifleman named Henry Bedinger marched in a second Virginia company, which was locked in an informal race to Cambridge with Morgan’s men. Led by Hugh Stephenson, the group set out from Mecklenburg, Virginia, now Shepherdstown, West Virginia, two days after Morgan, on July 17. Bedinger kept a journal while en route. This year, to mark the Beeline March’s 250th anniversary, Historic Shepherdstown published excerpts from the diary alongside an interactive map.

Need to know: How tarring and feathering worked

- Vigilantes covered the victim’s body in pine tar, which could blister or burn the skin, then added decorative feathers to embarrass them.

- The punishment wasn’t designed to be deadly, but it could be painful and humiliating.

Bedinger reported that Pennsylvanians brought his company vegetables when they camped in Littlestown on July 21. As they left another town two days later, he wrote, “we had shouting as usual.” At one point, a rifle mishap took place, with one soldier shooting another’s leg at a tavern. In New Jersey, rural country dwellers brought the troops beer, cider, buttermilk, apples and cherries, leading the men to fire their rifles in thanks. In New York, the company tarred and feathered an impostor claiming to be a rifle battalion colonel, then dunked him in a river.

Morgan’s company arrived in Cambridge on August 6, 1775. The captain later said that he was proud not to have left any men behind. (“Every place was full of people,” Bedinger wrote of Cambridge after Stephenson’s company reached the city on August 11, “most of them in tents.”) But with the Beeline March completed, Morgan grew frustrated, feeling he did not have enough to do in Massachusetts. His riflemen shot ball after ball into a seven-inch target from a distance of 250 yards, thrilling locals but causing trouble for the Continental Army’s commander, George Washington.

The future president was embarrassed by these undisciplined soldiers, even confiding that “he wished they had never come,” wrote John Adams in a letter. The riflemen’s behavior “is not what [Washington is] trying to create in this Continental Army,” says Parkinson. Still, he adds, “As people are watching the Beeline March, they’re paying attention to this phenomenon. They’re reading about it in newspapers in real time, and it’s beginning to create this mythology about these [riflemen].”

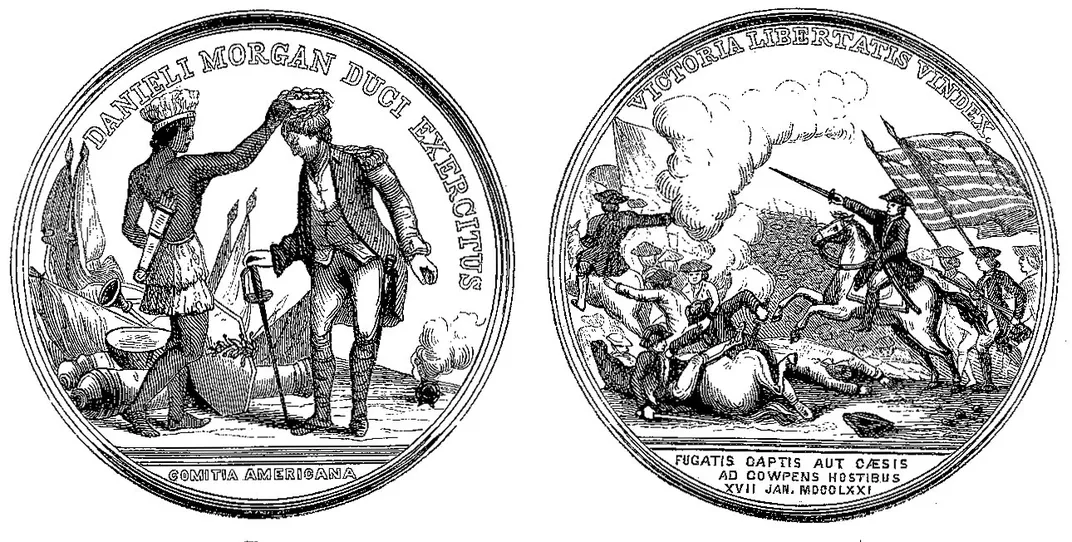

In September, Washington sent Morgan and his rifle company to Canada. After Benedict Arnold was injured during the Battle of Quebec that December, Morgan assumed command of the American forces but was unable to overcome the enemy. He was taken prisoner by the British, then released in early 1777. Promoted to the rank of colonel, Morgan, along with his riflemen, played a pivotal role in the American victory at the Battle of Saratoga later that year. Morgan was named a brigadier general in 1780 and is possibly best known today for his win over the British in Cowpens, South Carolina, in 1781.

A John Trumbull painting on display in the United States Capitol Rotunda depicts the British surrender at Saratoga in 1777. Morgan stands in the foreground, wearing a white garment that looks like a hunting shirt. Jacketed officers surround him. By then, the rifleman had earned Washington’s favor, with the commander describing him as a “good and valuable officer.” As Zambone says, “Washington’s idea of an ideal American soldier is someone who can be smart on parade but also can wear the hunting shirt.” (The historian notes, however, that Morgan was more likely wearing a regimental uniform during the surrender.) Trumbull’s portrayal speaks to the idea of Morgan as a leader of riflemen, someone with perhaps just a bit more swagger than his peers.

The Spanish motto inscribed on Morgan’s sword, now housed in the collections of the Virginia Museum of History & Culture, offers an apt portrait of the rifleman’s personality. Translated into English, it reads, “Draw me not without reason” on one side and “Sheath me not without honor” on the other.

After his storied military career, Morgan served as a Virginia congressman in the House of Representatives. He retired to Winchester, where he’d begun the Beeline March, and died at his home in the city in July 1802.