How Do You Wear a Gown Made of Glass? Marvel at the Eye-Catching History of This Unlikely Fashion Trend

In the 20th century, actresses and royals alike donned delicate dresses woven with spun-glass threads. More recently, celebrities have sported impractically fragile handbags on the red carpet

Key takeaway: Glass in fashion

Over the centuries, designers have incorporated glass into embroidered accessories, haute couture gowns and even bridal ensembles.

Oscar de la Renta’s intricate “shattered-glass” gowns have garnered double takes on the runway and the red carpet in recent months. First introduced in the label’s fall 2024 Art Nouveau collection, the frocks—inspired by Tiffany & Company’s iconic stained-glass designs—quickly became a signature look for the American fashion house.

Carefully crafted from thousands of hand-painted acrylic pieces, the dresses are neither glass nor shattered, but the illusion is convincing—and compelling. Between the play of light on the multifaceted surfaces and the trompe l’oeil effect of the eye-catching technique, these “glass” gowns create fashion moments as showstopping as Cinderella’s slipper.

But wearable glass isn’t a new trend; indeed, both men and women have been sporting it for centuries, and not just in high-tech accessories like watches and eyeglasses. The dangerous allure of this delicate fashion statement dates back to the pre-industrial age, when glass was a frugal (if fragile) alternative to jewels, bedazzling coats, cuffs, fans, buttons and buckles.

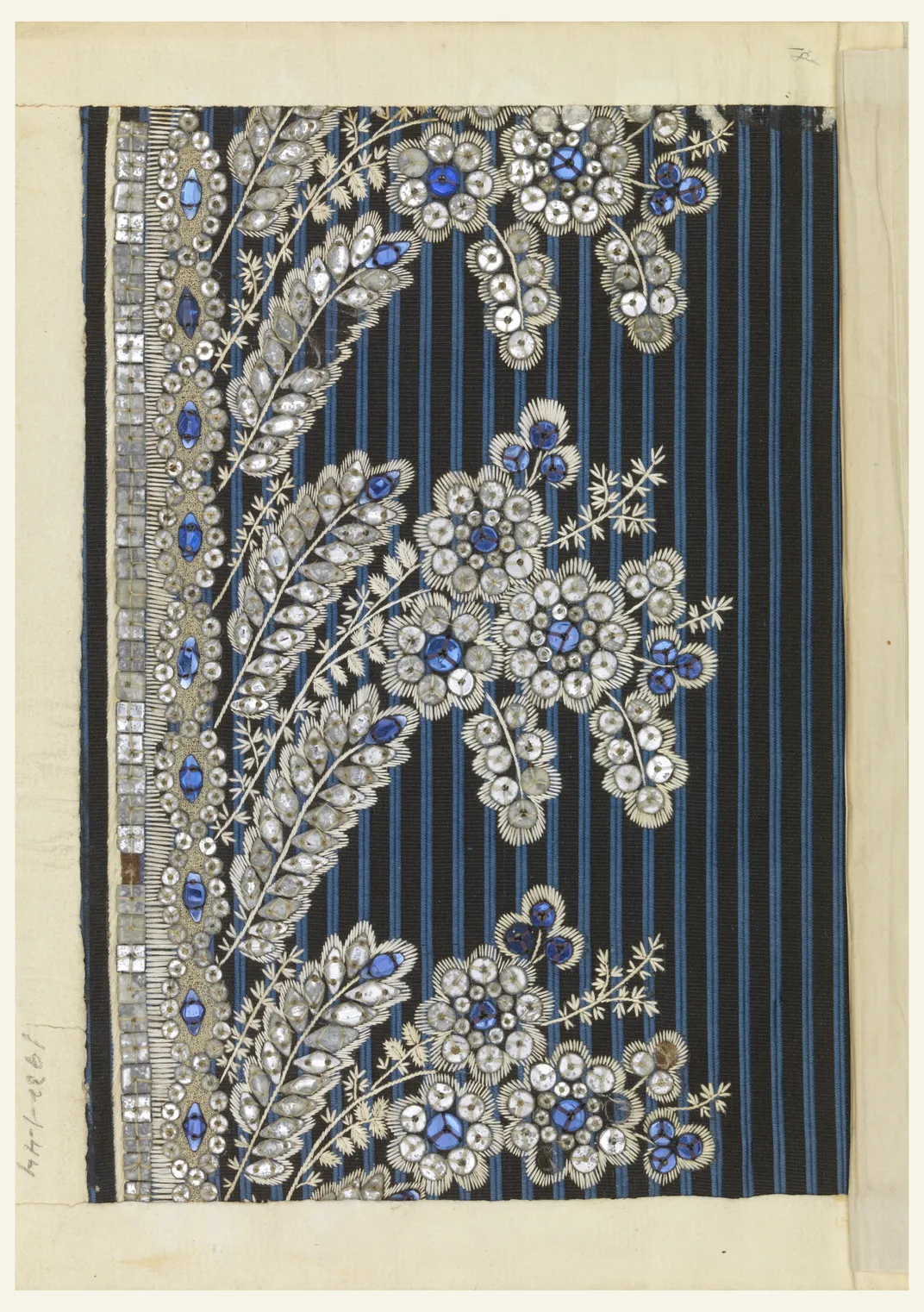

Glass “gems” could be mounted on silver or colored foil to lend them brilliance in candlelight, as illustrated by many surviving embroidery samples for men’s coats and waistcoats in the collections of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Unlike diamonds, though, glass wasn’t forever. In addition to cracking, the material could suffer from “glass disease” and become clouded over time, says Susan Brown, the New York museum’s associate curator and acting head of textiles.

The Victorians found a sturdier solution, using tiny colored glass beads—called “seed beads” or sablé, meaning “sandy” in French—to create elaborate pictorial coin purses, tobacco pouches and gloves. Dozens of examples depicting flowers, landscapes, people and animals have survived intact in the Cooper Hewitt collections. “They’re seemingly indestructible,” Brown says with a laugh.

Textile designers also dreamed of spinning glass filaments into riches just as Rumpelstiltskin spun straw into gold. Thin, flexible wisps of spun glass could be woven with silk fibers to produce fabric. The glass fibers created a “resplendent effect … that no moth can fret, or rust corrode, or sun or damp discolor,” an English newspaper reported in 1841. The previous year, London silk merchants Williams & Sowerby had demonstrated their patented glass-weaving process at an exhibition. But this material was likely intended for upholstery rather than clothing: A Lord Chesterfield ordered an embossed satin velvet and glass fabric to cover his chairs.

Still, it didn’t take long for spun-glass fabrics to infiltrate the female wardrobe. Philadelphia manufacturer Joseph Weed exhibited bonnets of spun glass and silk at the 1846 National Fair in Washington, D.C. Each contained 140,000 yards of glass thread and cost $20 (around $835 today). In 1879, a German newspaper reported that a Viennese glass artist had opened a shop selling “good, warm clothing” made out of spun glass, as well as “carpets, cuffs, collars, veils … [and] white, curly glass muffs and ladies’ hats of softest glass feathers.”

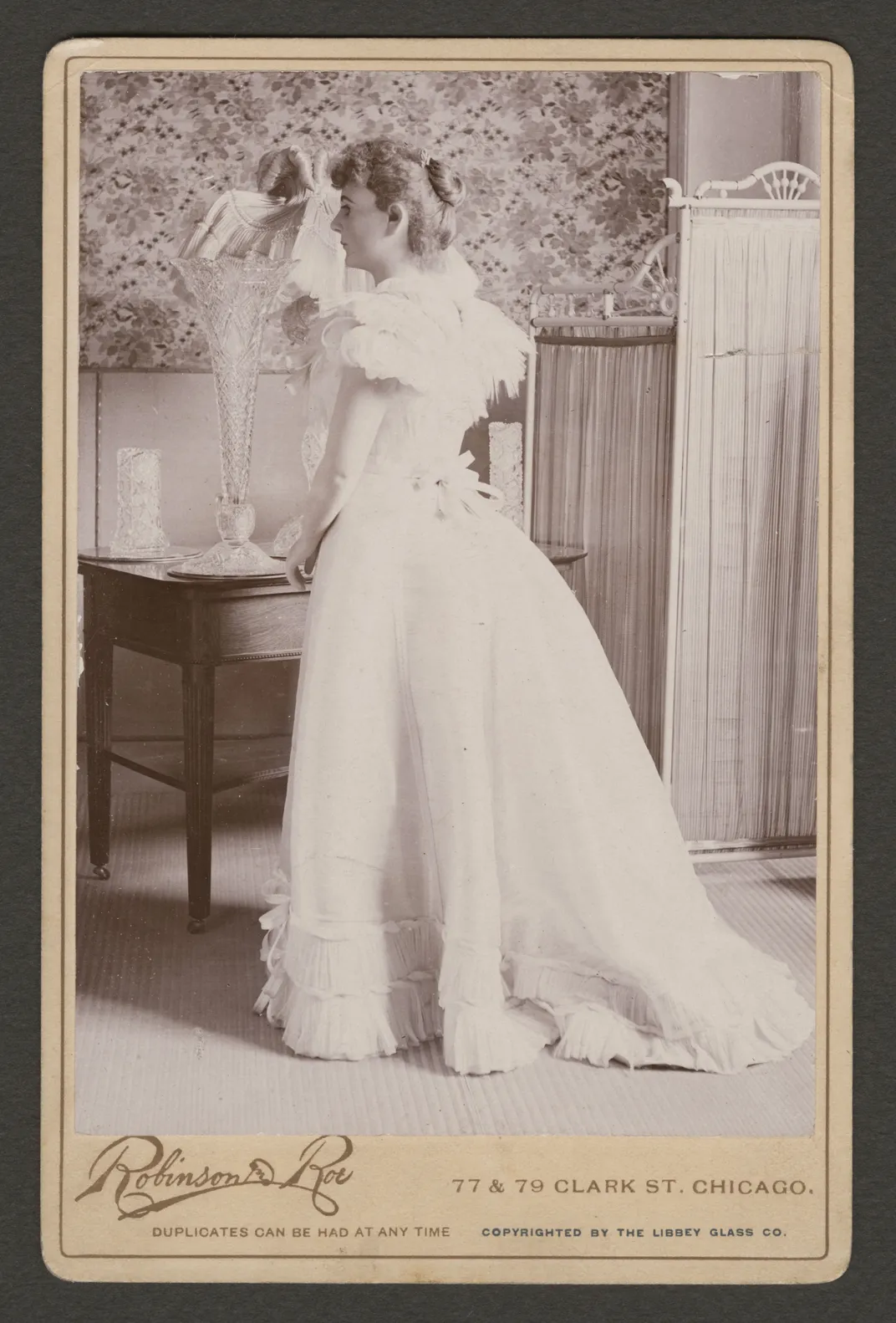

The Libbey Glass Company displayed a spun-glass gown and parasol made by Victorine Carmody at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Now housed at the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio, it weighs more than 13½ pounds. Infanta Eulalia of Spain visited the fair and ordered a replica (priced at a princely $2,500, or roughly $90,000 today) for her own wardrobe. “It is predicted that glass dresses for ladies will become a fad,” the New York Times noted.

Though spun-glass textiles were ultimately deemed too easily damaged (and too uncomfortable) for daily wear, they were ideal for the stage and the silver screen. Significantly, it was an actress, Georgia Cayvan, who had come up with the idea for the Libbey glass gown, and she wore it onstage at the Lyceum Theater in New York City, where it shimmered in the footlights.

Actress Alice White wore a spun-glass evening gown in the 1928 film Naughty Baby. According to contemporary coverage, the dress was not only woven with glass threads but also “covered with glass scales, some of them backed with mercury like tiny mirrors.” The translucent material was “ideal for film purposes because it reflects a higher ratio of light than any other fine-spun, irregular surface without causing halation,” the halo effect that bleeds from bright moving images.

Hollywood costume designers repeatedly returned to glass for its novelty and visual impact. The glamorous German actress Luli Deste wore a sparkling dress of spun glass when she made her American film debut as a French fashion designer in the 1937 movie She Married an Artist. “But it’s not as transparent as you might hope,” the Des Moines Register wrote. On set, Deste had to stand up between takes to avoid crushing the fabric. Inevitably, the flimsy frocks were mentioned in advertisements for these films. A promotion for Naughty Baby read, “See the spun-glass evening gown.”

Manufacturers continued to experiment with glass-infused textiles for the mass market. One gown was advertised in 1933 as being “no heavier than one made of taffeta, and the material may be cleaned with a petrol-soaked cloth and gently rubbed with soap suds.” Spun glass could also be knitted or crocheted to make “the most glamorous evening gowns,” according to a newspaper columnist. In the 1930s, innovative French knitwear designer Anny Blatt used shining white spun-glass yarn to hand-knit an evening gown, which she dubbed “White Lilac.” A red-and-black version with a frilled skirt was called “Spanish Nights.”

World War II encouraged technological experimentation and a widespread belief in better living through advances in chemistry. Lightweight, durable Fiberglas—patented in 1936 with just one “s” in its name—entered the consumer market and fueled America’s postwar housing, automotive and aerospace boom. The textile industry renewed its efforts to manufacture fabric from glass.

Stiff spun-glass textiles had long been used for petticoats and dress linings, which were worn sandwiched between undergarments and outerwear and did not touch the skin. In 1947, the lingerie firm Julius Kayser & Company staged a “futuristic fashion show” of tennis clothes, lingerie, lounging pajamas and “furs” made from gossamer textiles of spun glass mixed with horsehair, the London-based Reveille reported. There was even a barely there wedding ensemble complete with a spun-glass veil. But organizers stressed to the press that “the fashion show was merely a preview and that glass clothes [wouldn’t] be manufactured for the market for some time,” the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported.

Indeed, by the late 1950s, glass-fiber fabrics had been relegated to interior design, where they were primarily used in curtains. According to manufacturers, they were dirt- and mildew-resistant and wouldn’t stretch, shrink or fade in the sun. More important, they were fireproof. Midcentury architects “started to use big expanses of glass that needed big expanses of drapery,” Brown says. “That was a fire hazard. We start to see chemical fire retardants added to textiles, as well as experiments with Fiberglas.” But the new glass textiles couldn’t be ironed or dyed; they tore easily and required careful hand-washing.

In 1962, the Owens-Corning Fiberglas Corporation announced that “clothing made of fiber glass now is close to reality.” It exhibited prototype snowsuits, dresses and coats, claiming that “Fiberglas fabrics will be stronger and more shrink-resistant.” The company’s Beta yarn, introduced in 1963, promised to make glass-based textiles “80 percent more abrasion resistant.” Yet these fabrics were mostly used for table linens and bedspreads, not clothing. Persistent complaints about skin irritation from contact with such textiles—or clothes that had been in contact with them—prompted the Federal Trade Commission to enact measures like the 1972 Care Labeling Rule, which required washing instructions on all domestic and imported clothing and sewing fabric.

In the 21st century, an array of avant-garde fashion designers have been drawn to the beauty and ephemerality of glass, which serves as a meta commentary on the transience of fashion—and life itself. For a 2001 collection, Alexander McQueen created a scaly bodice out of glass microscope slides painted blood red, then paired it with an exuberant skirt of dyed red-and-black ostrich plumes, contrasting the brittle, angular shards with the soft, floating feathers. That same year, Hussein Chalayan’s models attacked each other with hammers on the runway, shattering what appeared to be glass garments. Dutch designer Iris van Herpen has used handblown glass bubbles, 3D-printed silicone and ultraviolet-transmitting Simax glass to fashion wearable sculptures that simultaneously reveal and conceal.

Glass lends itself to philosophical musings on impermanence and invisibility, but also to playful humor, reflecting and refracting human vanity and frailty. Like those who live in glass houses, those who wear glass garb must beware of throwing stones. In 2022, French fashion house Coperni collaborated with handblown glassmaker Heven on a deliciously impractical version of its minimalist Swipe purse, normally produced in leather. The $2,700 glass “it bag” went viral when several celebrities carried the heavy holdall on the red carpet. Although it was as impractical as Cinderella’s slipper, the breakable bag seemed to belong in an entirely different fairy tale: “The Emperor’s New Clothes.”