This Surprising Ancient Reptile Had a Colorful, Corrugated Sail on Its Back. New Research Suggests It Was Used to Communicate

A 247-million-year-old fossil from a German natural history museum reveals the secrets of Mirasaura

Key takeaways: What type of animal is the Mirasaura?

- This prehistoric reptile lived about 247 million years ago during the Triassic Period.

- Researchers have found that the Mirasaura had a fan-like sail on its back.

Some fossils are truly breathtaking. While paleontologists are used to finding scraps of bones, broken teeth and hazy footprints in ancient rock, every now and then, someone finds a fossil that allows us to envision what ancient life really looked like. Mirasaura grauvogeli is such a fossil creature—a 247-million-year-old reptile that beautifully demonstrates how peculiar scaly animals were becoming in the wake of Earth’s worst mass extinction.

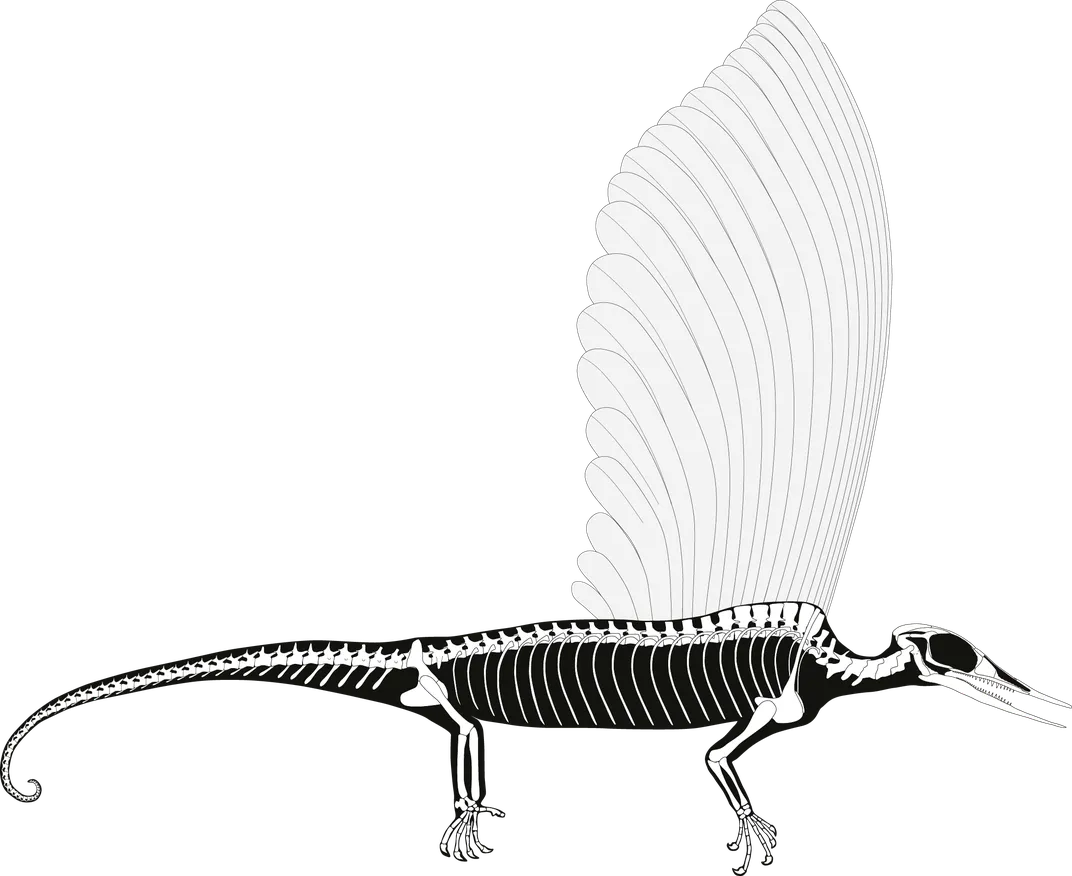

“It completely blew my mind when I first saw the small skeleton with the crest,” says Hans Sues, a paleontologist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. Preserved in tan stone, the fossil of Mirasaura included much of the ancient reptile’s skeleton and a feather-like fan that jutted from the animal’s back. As Sues and colleagues propose in a new Nature paper describing Mirasaura, the fossil both resolves a Triassic enigma and raises the possibility that prehistoric reptiles looked even stranger than their bones suggest.

Paleontologists had seen an animal like Mirasaura before. In 1970, paleontologist A.G. Sharov described a strange Triassic reptile found in present-day Kyrgyzstan that had long, feather-like structures jutting up from its back. Sharov named the reptile Longisquama insignis, with the genus meaning “long scales.” No one was quite sure why the reptile had long, thin structures jutting from its spine or even what kind of reptile it was. But the discovery of Mirasaura has finally offered a solution to the mystery.

“Longisquama was an oddball for many years,” Sues says. Part of the problem was that the fossil was not well preserved and had been covered in a consolidant by earlier paleontologists, which made it difficult to get a good look at the bones. Experts needed more fossils for comparison.

The missing fossil form was found in Mirasaura. In 1939, paleontologist Louis Grauvogel was searching the rocks of northeastern France for new fossils and he found multiple. Researchers initially didn’t know what the fossils represented. Perhaps they were fish bones, or insect wings. It was only after Stuttgart’s State Museum of Natural History in Germany acquired them in 2019 that experts took a close look and realized that the fossils represented an unusual reptile with a sail back, Mirasaura.

“It’s amazing that this discovery was made from 80-year-old specimens that were already in a museum,” says Yale University evolutionary biologist Richard Prum, who was not involved in the new study. The fossils reveal what must have been an extraordinary creature, Prum says, with a sail almost as long as its own body.

Sues and colleagues found that Mirasaura and Longisquama are each other’s closest relatives in the family tree of prehistoric reptiles. Both had prominent, sail-like structures on their backs, and both had the anatomical hallmarks of a bizarre group of reptiles called drepanosaurs. Sometimes called “monkey lizards,” drepanosaurs only lived during the Triassic, between 201 million and 252 million years ago, and had a strange combination of features. Their skulls are long and almost bird-like, with chameleon-like bodies and appendages that suggest they were most at home in the trees. Some species even had a claw at the end of their tail. Now, thanks to Mirasaura and Longisquama, experts know that drepanosaurs also sported elaborate structures on their backs.

Despite looking superficially feather-like, the sails on the backs of Mirasaura and Longisquama are not feathers at all. Nor are they quite like the scales covering other reptile body parts. The structures look corrugated, almost like cardboard. They also preserved tiny, pigment-carrying orbs called melanosomes, which more closely resemble the melanosomes that give birds their colors than those found in reptilian skin. With their sails, Mirasaura had evolved something that paleontologists have never seen before in any other reptile, or even any other land-dwelling vertebrate.

The sail of Mirasaura was very tall—about as tall as the animal’s length from its snout to its hips. Its prominence raises the question of why Mirasaura and other drepanosaurs evolved such a structure.

“I think the crest appendages in Mirasaura and Longisquama were most likely used for display,” Sues says. The distribution of melanosomes suggests that the sails were “conspicuously colored,” Sues says, and were likely used to communicate with other members of their species.Most other drepanosaurs are only known from bones and partial skeletons. Soft tissue preservation is both relatively rare and difficult to spot in the fossil record. Still, the discovery that both Mirasaura and Longisquama had such fan-like sails hints that other drepanosaurs did, as well. In the initial paper that described Drepanosaurus in 1979, Sues notes, “there is a passing mention of structures along the back.” A second look at that fossil might reveal a similar sail.

The significance stretches beyond the “monkey lizards.” The Triassic was a pivotal time for the evolution of new body coverings. Not only were scaly reptiles proliferating, but the predecessors of mammals were also evolving fur and whiskers. Dinosaurs and the winged pterosaurs, too, had inherited fluffy, fuzzy feathers from their common ancestor. Now Sues and colleagues have found yet another form of novel body covering among the drepanosaurs: modified skin adapted into a broad fan.

“The Mirasaura research teaches us that reptilian skin has evolved the capacity to generate many new kinds of skin appendages,” Prum says, ranging from feathers and scales to glands, horns and other structures. “The amazing spinal crest of Mirasaura is a unique and profoundly weird addition to this list,” he says.

The discovery is a reminder that many prehistoric organisms probably looked significantly different and more elaborate in life than what researchers can see from just their bones. The Triassic was a time when various organisms, especially reptiles, were going through an evolutionary burst that involved body coverings and display structures, also hinting that the ancient organisms were more behaviorally complex than previously thought. Imagining the little Mirasaura turning a colorful sail to the light on a tree branch provides a glimpse of what wonders remain to be uncovered.