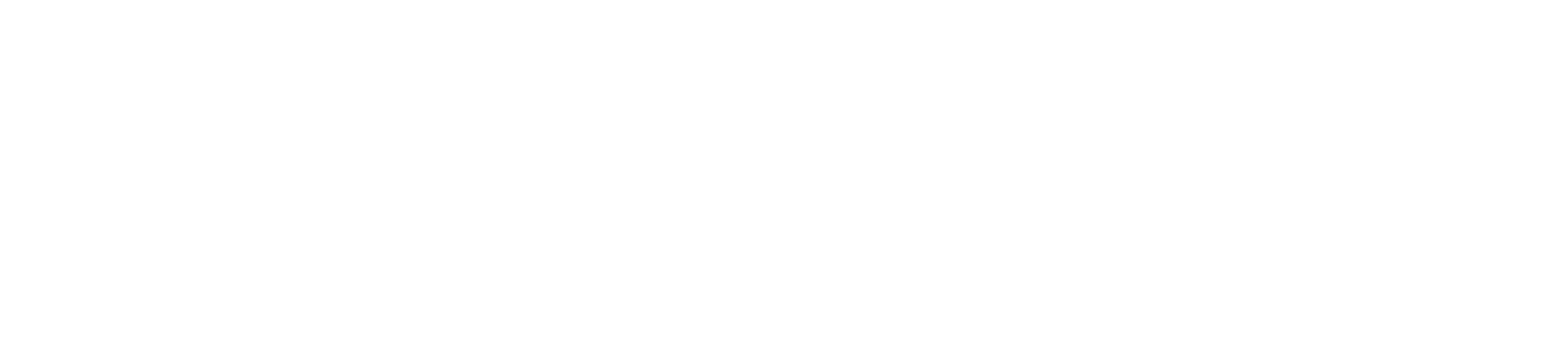

Los Angeles’ 1936 ‘Bum Blockade’ Targeted American Migrants Fleeing Poverty and Drought During the Great Depression

The two-month patrol stopped supposedly “suspicious” individuals from crossing into California from other states. But its execution was uneven, and the initiative proved controversial

Key takeaways: Los Angeles’ 1936 “Bum Blockade”

- In February 1936, the Los Angeles Police Department dispatched 136 officers to points along California’s border with neighboring American states, granting them broad authority to stop those deemed “suspicious.”

- Critics argued that the so-called Bum Blockade was unconstitutional. Financial woes and legal troubles ended the program after just two months.

When officers from the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) stopped an unkempt, dust-ridden man at the Arizona-California border before dawn on February 10, 1936, they wanted to know who he was and where he was from, as well as how much money he had to his name.

The man was John Langan, a Hollywood director with a penchant for prospecting, and he was on his way home from viewing mining properties in Arizona when he and a companion encountered the police around 5 a.m.

Langan objected to the interrogation, questioning if these officers had the authority to stop him in Blythe, a California desert town more than 200 miles east of Los Angeles. For his defiance, the police detained Langan, who became one of the thousands of American citizens stopped, arrested or turned away by the LAPD during a two-month border patrol known as the “Bum Blockade.”

Spearheaded by the department’s chief, James Edgar Davis (nicknamed “Two-Gun”), the operation targeted individuals who weren’t permanent residents of California or were believed to have no way of supporting themselves—in other words, the poor, unemployed migrants who flocked to the state during the Great Depression. The blockade was “designed to halt the seasonal influx into California of migratory indigents, among whom are believed to be scores of criminals and disease-carrying ne’er-do-wells,” the Los Angeles Times reported on February 4, 1936.

“This wasn’t just about migrants coming into California,” says Bill Lascher, author of The Golden Fortress: California’s Border War on Dust Bowl Refugees. “It was also about cleaning up the streets of Los Angeles and criminalizing homelessness.” While some members of the public supported the blockade, others criticized its constitutionality, setting the stage for a debate with clear parallels to present-day immigration issues.

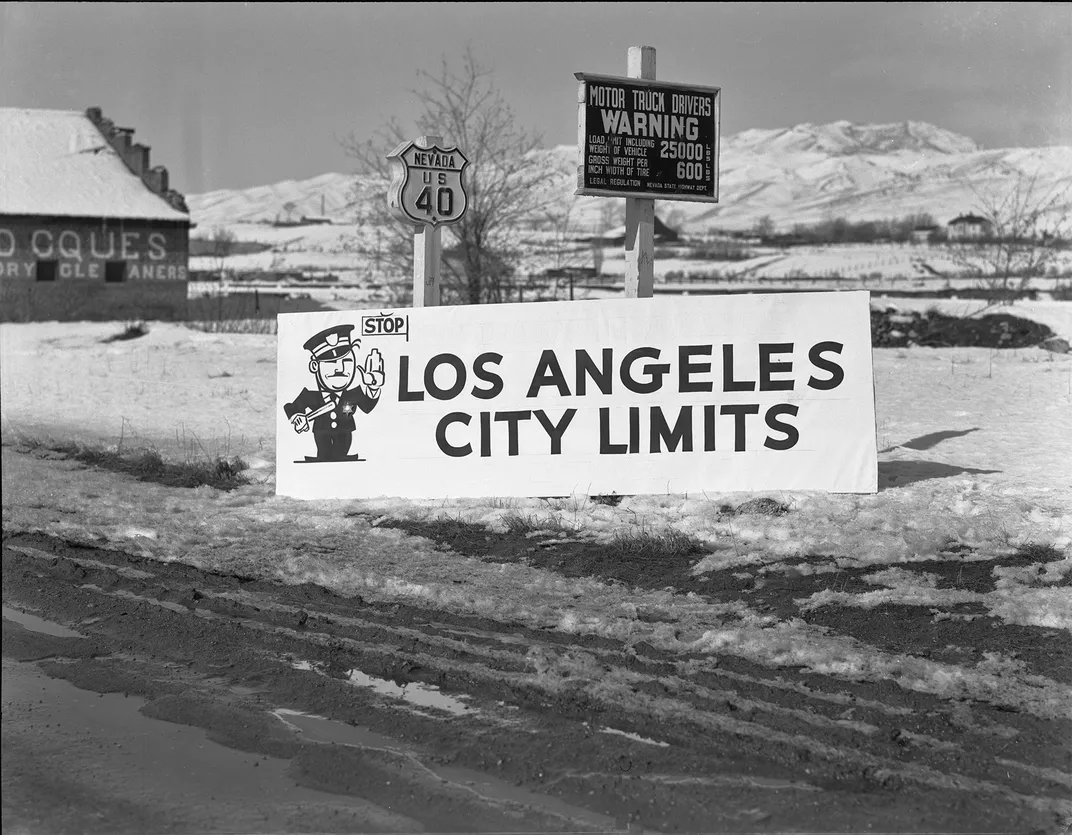

Migrant workers in California during the Great Depression

The Bum Blockade unfolded against the backdrop of a mass exodus from the Great Plains, which spans parts of Oklahoma, Texas and Kansas, among other states. During the 1930s, roughly 2.5 million Americans from rural farms and big cities alike packed their belongings and left their hometowns in search of employment and stability, with some 200,000 to 400,000 choosing California as their destination. Many were blue- and white-collar workers affected by the Great Depression. Others were tenant farmers leaving behind the deadly droughts and storms of the Dust Bowl.

California’s growth in the early 20th century, especially in the city of Los Angeles, attracted many settlers to the state. The agricultural industry boomed in the 1930s, with more than half of the nation’s oranges, grapes, walnuts, carrots and lettuce coming from California’s farms, which were staffed largely by seasonal migrant workers.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, most of these farm workers were immigrants from foreign countries, including China, Japan and Mexico. But nativist sentiment and anti-immigration laws pushed each of these groups out of California in turn, culminating in the Depression-era Mexican Repatriation. To open up jobs for white Americans, state and local governments deported or forcibly relocated about 1.8 million people of Mexican descent across the United States. Roughly 60 percent of these individuals were U.S. citizens.

The supposed bounty of agricultural jobs created by these coercive departures inspired out-of-work Midwesterners to head to California. Those who found employment out west often encouraged their friends and family to make the journey, too. “They write back about their groceries and the cash,” Claude Bronson, who moved from Oklahoma to California in 1935, later recalled to an interviewer. “They say, ‘I’m gettin’ so much better help here than my folks back home.’ And then the folks begin to say, ‘I ain’t gittin’ enough here.’ That starts them right on out. I’ve heard so many talkin’ that-a-way.” California’s labor market quickly became oversaturated.

Hard times in the Golden State

Despite its mild climate and longer growing season, California was struck hard by the Great Depression. In 1932, farm income in the state dropped to less than half of its 1929 level. By 1934, around one-fifth of Californians were on public relief. Businesses and officials started promoting seasonal tourism over permanent relocation to the state.

As early as 1931, state government employees passed out cards at the Southern California border with neighboring states, informing newcomers that “there are no jobs open here, and that when there are, only bona fide residents are taken to fill them,” the Los Angeles Times reported.

“There’s a lot of competition for work, because agricultural production is also shutting down under different New Deal programs, which are encouraging farm owners to not plant as much as they had [previously],” says James Gregory, a historian at the University of Washington and the author of American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in California. “So [migrants] run into a bad job situation.”

Referred to as “Okies” even if they weren’t from Oklahoma, these migrants—almost all of them white—had trouble fitting in. To locals, “Okies were ignorant, uneducated, dishonest and strange,” notes the California State Capitol Museum on its website. “Some wanted to help the Okies by providing food and clothing. Others wanted them to leave California and go back home. Both sides agreed that the newcomers were not prepared for life in California.”

Many migrants found themselves out of work and living in shanty towns or “Hoovervilles” named after President Herbert Hoover. A 1933 survey recorded 101,174 homeless people in California at a time when the state’s population was just 5.7 million.

The Federal Transient Service, a New Deal measure introduced in 1933, helped support those who couldn’t find immediate work upon their arrival in California, establishing dozens of shelters, camps and “family bureaus” across the state. But when the program was cut in 1935, the funding gap offered reactionary Los Angeles politicians the opportunity to portray the migrants as a burden on already-strained resources.

“With state and local relief agencies scrambling to fill the void left by the federal government’s sudden departure, they again argued that migrants might overtax public institutions,” writes Lascher in The Golden Fortress. “The risk, they insisted, was [that] those left out of state-driven relief schemes would prey on local citizenry to survive.”

Instead of framing the situation as a repudiation of aid seekers, critics of public relief efforts “could present themselves as advancing local interests by focusing on supposed dangers from afar,” Lascher adds in his book. As Los Angeles Mayor Frank L. Shaw told the Sacramento Bee in February 1936, “It is important to note that Los Angeles is facing a desperate situation if we permit every incoming freight train to bring us a new shipment of unemployed, penniless vagrants to consume the relief so seriously needed by our needy people and to create a crime menace almost beyond conceivable control.”

The Los Angeles Police Department’s 1936 “Bum Blockade”

Davis, the Los Angeles police chief, formed a committee of like-minded individuals, including local business leaders and politicians, to discuss the migrant issue in November 1935. In a report, Davis and his fellow reactionaries outlined recommendations to deal with the influx of so-called “indigent alien transients,” including “the establishment of vagrancy penal camps” and “the policing of the common carriers and main arterial highways or other means of ingress into the State of California.”

The committee hoped that state and local agencies would help enact these proposals. But after these groups rejected the recommendations, Davis took matters into his own hands and began the Bum Blockade, citing a 1933 anti-indigent state law as justification for his course of action. Though Davis contacted sheriffs in multiple border counties to deputize his LAPD officers and legitimize the blockade, only three agreed to his request.

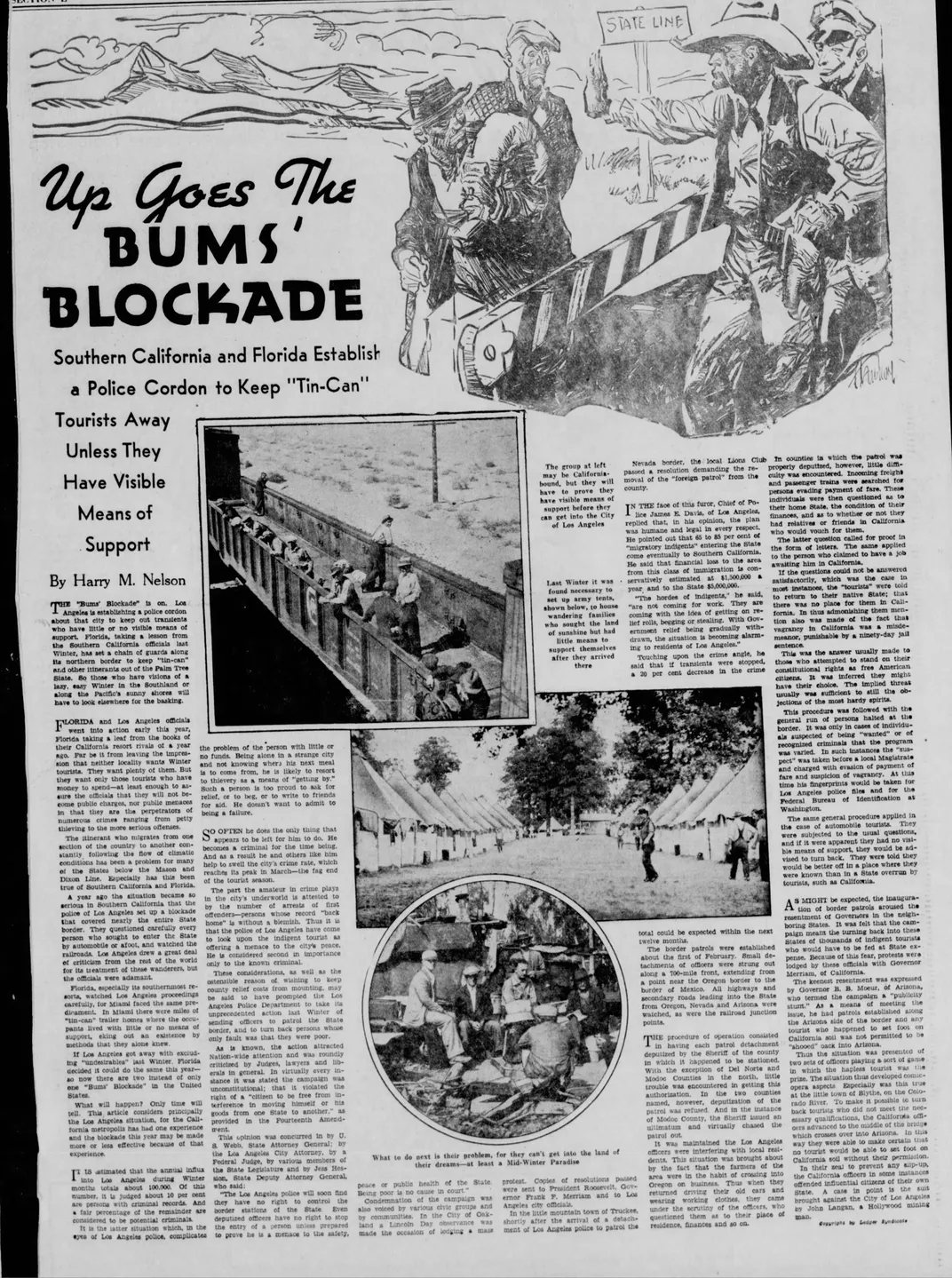

Beginning on February 3, 1936, the LAPD sent 136 officers to patrol 16 points along California’s 700-mile border with Arizona, Nevada and Oregon. “Veritable Army Corps Formed,” read the February 4 front page of the Los Angeles Times. Working with railroad executives and county sheriffs, these officers stopped trains, vehicles and hitchhikers, turning away those they deemed suspicious. Though Davis claimed the blockade refused entry to around 11,000 people by March 31, historians have since cast doubt on this figure, suggesting the actual total was much lower.

The patrol’s criteria for determining whether someone “belonged in California” was vague and largely up to individual officers’ discretion, writes Lascher in The Golden Fortress. He explains:

Most detainees exhibited some subjective characteristics of poverty, such as piles of weather-beaten luggage teetering atop a rickety jalopy or bindles sagging behind weary men hiking into the state. … Officers tended to wave shiny new Packards through their checkpoints but halted sputtering early-model Fords pulling makeshift trailers and caked with half a continent’s dust.

During the initial stop, officers fingerprinted the potential detainees to check if they had criminal records. Some who didn’t have warrants out for their arrest received the option of turning around and leaving California. Others were sent to “jails that might be little more than makeshift cells in rooms rented at off-season hotels in communities near the checkpoints,” according to Lascher’s book. Before long, the stream of migrants flooding into California had slowed significantly.

“The ‘California, Here I Come’ marching song of penniless wanderers faded away to a faint whisper in Arizona today,” United Press observed on February 6. The previous night, the news agency reported, officers stopped three trains in Yuma, Arizona, detaining 14 “transients.” That same evening, just 20 or so people lingered at a hobo “jungle” in Phoenix that usually hosted nearly 100 overnight guests.

As the Bum Blockade policed California’s border, Davis simultaneously continued to enforce harsh vagrancy laws in Los Angeles itself, searching for “indigents who can be prosecuted as vagabonds,” according to the Los Angeles Times. On February 8, the LAPD arrested 122 people deemed to fit these parameters, many of whom Davis claimed had criminal records.

What happened to detainees after their arrest? A week into the blockade, Davis announced plans to put the migrants—many of them imprisoned in penitentiaries far from the state line—to work, assigning them to unpaid, forced manual labor like quarrying rock, sand and gravel for public projects.

The public response to the Bum Blockade

Though some entities, such as the Los Angeles Times and the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, supported the Bum Blockade, others questioned the initiative’s constitutionality.

“We have an idea that a man without even so much as a plugged nickel in his pocket has a right to walk from here to there and back again in the United States, even if a state line intervenes,” wrote a columnist for the Los Angeles Daily News. Another journalist argued that the blockade “violates every principle that Americans hold dear … the right of any citizen to go where he pleases.”

The governors of California’s neighboring states, Nevada, Oregon and Arizona, also objected to the blockade, albeit for a different reason: They didn’t want to deal with a migrant crisis on their own borders.

“What the Los Angeles police are trying to do is completely illegal and unconstitutional, and they know it,” Arizona Governor Benjamin Baker Moeur told the International News Service. “They are simply trying to scare travelers away by threats of fingerprinting and jail.”

Arizona Attorney General John L. Sullivan even threatened to take legal action in response to the blockade.

“We will resist any attempt by California to get rid of its indigents by sending them back here,” Sullivan said in a statement. “If California wants to take indigents on her side of the border and put them in ‘bullpens’ and work them, that’s their affair, although it’s a rather strange interpretation of their advertised invitations to the world to come and bask in the sunshine and orange groves.”

Some counties in California objected to the imposition of Los Angeles police officers on their borders. Sheriff John C. Sharp of Modoc County reportedly gave Davis’ men a deadline to leave his domain after they harassed several local citizens. “I’ve stood for a lot and tried to be fair, but you have violated all the rules of decency,” he told an LAPD sergeant. “If you’re [still] here, there will be consequences.” Davis finally ordered his men home from Modoc on March 11, a full month after Sharp delivered his ultimatum.

The broader statewide Bum Blockade fizzled out in April, within two months of its start. Lawsuits filed against the LAPD and scrutiny of taxpayer dollars used to fund the blockade resulted in bad press, as did a statement from California Attorney General Ulysses S. Webb, who said the Los Angeles police had “no jurisdiction beyond the city’s territorial limits.” Webb added that Davis had no right to deputize his officers in other counties, nor “interfere with the duties devolving upon police of other governments.”

Despite the public blowback, Davis claimed the short-lived blockade as a win, telling the Associated Press that it “was directly responsible for [the] absence of a seasonal crime wave in Los Angeles for the first time in many years.” Outside observers argued otherwise. As the State Relief Administration of California noted in an August 1936 survey, a report produced by Davis earlier that year contained “much irrelevant data,” including two tables that showed crime decreasing as the number of “transients coming into the state was increasing.”

“If these two sets of figures have any connection,” the government agency reported, “they would seem to indicate that an increase in transients leads to a decrease in crime, a conclusion which even the friends of transients would scarcely draw.”

The legacy of the Bum Blockade

After Langan, the Hollywood director and mining investor, was stopped by the LAPD toward the beginning of the Bum Blockade, he decided to take legal action against Davis. With the help of the Southern California chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, Langan sued for $5,000 in damages. His complaint, according to the Pasadena Star-News, questioned the legality of Davis’ blockade and asked the police chief to justify his usurpation of “the duties of jailor, judge and jury.” But Langan dropped the case the following month, frightened into silence by an LAPD lieutenant who threatened him and his family. (The lieutenant was later found guilty of conspiring to murder a former cop who had been investigating corruption within the LAPD; the 1938 scandal forced Davis to resign as the department’s head.)

California wasn’t the only state to assert its authority over migrants during the Depression. On April 18, 1936, for example, Colorado’s governor declared martial law and closed his state’s borders to migrant workers from adjoining states, as well as Mexico. Unlike the California blockade, which chiefly targeted white migrants, Colorado’s ban mainly affected those of Mexican descent. The measure proved unpopular, and the governor was forced to rescind his decree after just ten days.

What made the Bum Blockade unique was the fact that its “animosity” was directed toward “white Americans of longstanding American nativity,” says historian Gregory. “They’re not immigrants from other nations. They’re not Black or Latinx. They’re white, and that’s different than almost any of the other … migration crises, fears, that we could think of.”

Gregory argues that the broader public response to migrants fleeing poverty and drought during the 1930s speaks “to a syndrome that … parts of the United States continue to manifest, where fear of outsiders becomes a political issue and is used politically to gain advantage in elections and elsewhere.” When people look back on these polarizing chapters in American history, Gregory adds, they say, “‘Oh, well, that was really wrong. That was really bad. We should never do that again.’ But guess what? We do it again.”