Seven Mysteries You Can Explore in America’s National Parks

From unexplained phenomena to baffling disappearances, follow the clues while discovering our country’s treasured protected areas

It felt like paddling through soggy cereal. My wife and I were deep within Everglades National Park, struggling to kayak past dense mats of periphyton, a mass of algae, fungi and other organisms. Making matters worse, numerous water trail markers were missing, seemingly swept away by recent hurricanes. After several confusing detours, the sun was getting low, and we were getting worried.

We carried a map, compass and headlamps, but we had no desire to navigate through this enigmatic landscape after dark. Fortunately, the periphyton let up, and the markers returned. The final mile of our six-mile jaunt took us through intriguing mangrove tunnels and channels of dark water. Approaching the boat landing, we enjoyed a beautiful sunset from the water.

We’d come to South Florida to investigate several mysteries related to the Everglades’ tortured past. Seminole refugees once hid from the U.S. Army in these wetlands. Rum runners moved their contraband through here during Prohibition. In the late 1800s, plumage poachers hunted subtropical birds to near-extinction before being stopped. Bodies regularly turned up, typically swept here by floods but sometimes dumped by criminals. There’s even a Cold War missile site, if you know where to look.

During the early 20th century, most residents surrounding the Everglades considered it a worthless swamp that should be drained and developed. Then, conservationist Marjory Stoneman Douglas changed public perceptions with three little words, and the “River of Grass” was recognized for being a dynamic ecosystem worth protecting as a national park beginning in 1947.

By the numbers: America's National Parks

- The National Park Service consists of 433 units and counting.

- The system covers 133,000 total square miles of land and water across all 50 states, the District of Columbia and U.S. territories.

Yet old legends linger, and people still talk about a lost city of the Everglades, where gangster Al Capone may have had an outpost. Is it just a rumor, or could there be some truth behind the tale? In this case, Capone’s Outfit left no records to help us. But keep your eyes peeled around the ghost town of Pinecrest, on the Loop Road in the adjoining Big Cypress National Preserve, and you might spot the ruins that locals believe were owned by the infamous mobster.

As we drove away, I considered how many fascinating mysteries I had come across while exploring National Park Service sites over the years. Some stories happened inside famous national parks, like that of the 1920s couple, Glen and Bessie Hyde, who vanished while rafting the wild Colorado River through Grand Canyon National Park. Other tales came from little-known units like Dinosaur National Monument on the Colorado-Utah state line, which was home to legendary frontierswoman Josie Bassett, who was accused of being a bootlegger and tried and acquitted for cattle rustling.

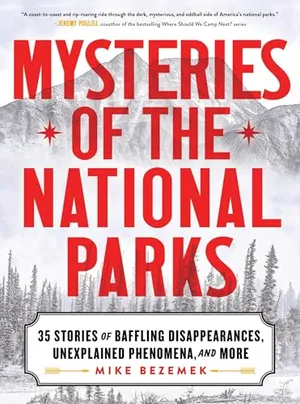

To unravel these stories, I hit the ground to follow the clues through our national parks, researching what became my new book, Mysteries of the National Parks: 35 Stories of Baffling Disappearances, Unexplained Phenomena and More. In this book, I present infamous crimes, buried treasures and hidden histories from across the entire National Park System, currently 433 units and counting amounting to 133,000 total square miles of land and water. That adds up to a lot of wild, undeveloped and historic territory where many unexpected things have happened. Along the way, I share travel tips for visiting these parks and bringing the puzzles to life.

Beyond the Everglades, here are six more enigmatic questions you can ponder in our national parks.

What happened to the Lost Colony of Roanoke?

Several years ago, my wife and I were road-tripping through the Outer Banks of North Carolina when we stopped at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site. This smaller and lesser-known National Park Service unit preserves the site of a better-known story that helped inspire my new book.

The Lost Colony was the first English settlement in North America—until it mysteriously vanished from Roanoke Island sometime after its establishment in 1587. In 1590, a long-delayed relief party arrived to find the townsite abandoned. They saw no signs of violence, and two carvings on trees suggested the colonists had relocated south to live with the Croatoan tribe. That night, the relief party’s ship was blown to sea, ending their search.

All subsequent efforts to locate the colonists failed for various reasons, and rumors of their fate ranged widely. Some said they lived peacefully among local tribes for decades. Others told tales of an English-style village hidden in the pine forests of the mainland. Some stories spoke of a massacre. Yet for years to come, visitors to the area would report encounters with local tribespeople, and tales of their ancestors, who had European features.

Today, it’s an excellent park with indoor and outdoor exhibits, including a nature trail winding through the original site and a reconstructed earthen fortification. An outdoor theater shows the long-running symphonic drama The Lost Colony. Nearby, the Freedom Trail leads to the site of the Freedmen’s Colony, home to formerly enslaved African Americans after the Civil War.

Did a private pilot spot the first flying saucer above Mount Rainier?

On a sunny afternoon in June 1947, a private pilot named Kenneth Arnold was flying his small plane through the skies above Mount Rainier National Park. Peering down at the dormant volcano, he searched the icy slopes for wreckage from a recent military crash.

Suddenly, a blinding flash illuminated the cabin. A stunned Arnold reportedly watched as a chain of nine bright objects flew toward the mountain at incredible speeds. He said they were shaped like crescent moons and moved erratically, like saucers skipping across water. After Arnold landed in Yakima, his story spread quickly across a war-weary nation, with one newspaper coining the infamous term “flying saucer.”

The resulting mix of mystery and mass panic would spawn a worldwide craze, leading to countless UFO reports, hoaxes and sci-fi depictions. A controversial military investigation was followed by conspiracy theories that introduced the concept of so-called men in black. Meanwhile, the infamous Roswell incident in New Mexico happened exactly two weeks after Arnold’s sighting. Ultimately, most incidents could be easily explained, but not all.

Today, you can visit the scene of the first modern UFO sighting at Mount Rainier National Park, 60 miles south of Seattle. Head to the popular southern side of the park, around the Henry M. Jackson Memorial Visitor Center, where scenic drives and hiking trails offer stunning views of the mountain. To further bring this mystery to life, consider hiking or biking the old Westside Road, a partially paved abandoned highway project. After four miles (one way), you’ll reach the Marine Memorial, which offers views of the Tahoma Glacier. Still entombed in the ice is the wreckage of the military plane—along with the bodies of 32 servicemen—that Arnold was searching for in 1947.

How could a sand dune swallow a boy?

It was a hot summer day in 2013 at Indiana Dunes National Park, when a pair of dads led their sons in a footrace up the slopes of Mount Baldy. About midway, a young boy named Nathan Woessner diverted to examine a small hole in the sand. Suddenly, he plummeted feet first into the void and was gone. When the dads tried to claw away the sand, the hole collapsed. This set off a frantic dig involving bystanders and authorities—a race to save Nathan before it was too late.

For thousands of years, the southern shore of Lake Michigan has been lined by massive sand dunes. Over time, most of these dunes were naturally stabilized by grass and trees. Yet Mount Baldy remained an outlier, a giant pile of bare sand. From offshore winds, it gradually migrated inland, covering structures and trees in its path. Though no one realized it, for years, strange holes had been appearing on Mount Baldy, only to quickly collapse and vanish.

Nathan had fallen 11 feet deep into one such void, created by a tree trunk that had decomposed inside the dune. Fortunately, this left an air pocket, and the boy was rescued alive. Some observers later pointed out that this hazard of the natural world had long been known about colloquially as a “devil’s stovepipe.” However, the general public remained unaware. Even modern scientists had yet to recognize the features, with subsequent academic research in 2015 terming them dune decomposition chimneys.

Today, the park service monitors for these dangerous voids in the sand, restricting visitor access on Mount Baldy to ranger-led hikes that are typically held during the summer season. The rest of the park trails and beaches are unrestricted, offering a chance to explore this dynamic landscape next to the Great Lakes.

Why did the cliff dwellers of the American Southwest abandon their stone palaces?

Snow was falling in large flakes as two cowboys rode through the high country that later became Mesa Verde National Park. It was mid-December 1888, and the pair was searching for stray cattle along the bluffs above a deep canyon. Instead, they spotted something concealed in nearby cliffs that would change the course of history in the American Southwest.

Bathed in overcast light, the ruins of a stone city stood out from the shadows of a massive alcove. The cowboys climbed down to investigate what they named the Cliff Palace, finding it covered in a thick layer of dust that had accumulated for centuries. They’d heard rumors about these vast cliff dwellings but never seen them until now. In fact, their Ute neighbors had warned the white settlers to avoid these sacred ruins.

But this was the Wild West, and the settlers’ goal was profit. So, these cowboys became amateur archaeologists, triggering a relics rush that would come to rival the greed of gold. In time, settlers would excavate and plunder countless ancestral ruins across the Southwest, with artifacts carried off to private collections and museum displays.

Legends were told of the Anasazi, the “old ones,” who had mysteriously vanished from the cliff palaces without a trace. However, this was an invented story, essentially marketing copy, used to sell guided tours and stolen relics. In reality, the cliff dwellers had been Ancestral Puebloans who had migrated south to the modern pueblos in New Mexico and Arizona.

Throughout the 20th century, as ruins plunder shifted to protecting the cliff dwellings, archaeologists tried to decipher the remnants and make amends with the descendants, while understanding the ancient situation that prompted this mass migration. With the help of new excavations made at undisturbed sites inside and outside the park, the story of Mesa Verde and the cliff dwellers’ abandonment continues to emerge today.

Paleoclimatic data suggests a 13th-century shift from a warmer and wetter period to numerous decades of drier and increasingly colder conditions. Combined with natural resource depletion, this may have caused failed crops and societal conflicts. So, the Ancestral Puebloans gradually sought out warmer climates at lower elevations. By the early 1300s, Mesa Verde was abandoned.

To bring this mysterious national park to life, visitors should allow time to join a ranger-guided hiking tour of the largest ruins complexes, such as Cliff Palace, Long House, Balcony House and Mug House. Other highlights include early pit houses and pueblos, such as Mesa Top Loop and Far View Sites. Particularly worthwhile excursions include the Mesa Verde Museum and especially the Long House Loop.

What created the Appalachian balds?

Across the southern Appalachian Mountains, dozens of mysterious bald peaks rise above the Blue Ridge Parkway and surrounding forest. They can be found from northern Georgia across western North Carolina and into southern Virginia. Given the prevailing conditions, including relatively low elevation, mild climate and good drainage, one would expect these bald peaks to be timbered.

In fact, some bald peaks stand adjacent to tree-covered summits, and the reasons why one is bare and another is forested remains a mystery. It’s not even clear when the balds first appeared. References to the balds in Cherokee legends, as recorded by ethnographer James Mooney, suggest they’ve been there since ancient times. Colonial explorers and surveyors recorded that the balds were present in the late 1700s, before widespread European settlement.

Scientific origin theories have ranged widely over the decades, from ice storms to lightning fires. However, during the early 20th century, various balds were protected by national forests and parks, and in places where livestock grazing was restricted, those balds began to shrink from vegetation encroachment. This was an important clue to a developing theory that grazing megafauna—such as the extinct mammoths and mastodons that once roamed the southern Appalachians—may have played a role. Further studies will be needed to unravel the mystery.

In the meantime, one of the best ways to explore the Appalachian balds is along the Blue Ridge Parkway. Many bare peaks rise above this 469-mile National Park Service route that follows the crest of the Blue Ridge Mountains through Virginia and North Carolina. One popular hiking area is found in the latter state, near mile marker 420, on Black Balsam Road. From the trailhead, the Art Loeb Trail leads to several bald peaks offering panoramic views in the Great Balsam Mountains.

Was Upheaval Dome created by a meteorite impact?

In the 1990s, a field team led by planetary geologist Eugene Shoemaker arrived atop the Island in the Sky District of Canyonlands National Park in Utah. Their goal was to settle the debate, once and for all, about what created the enigmatic Upheaval Dome. Though its name can suggest otherwise, this bizarre structure is actually a three-mile-wide depression carved into the sandstone mesa, resembling a massive bullseye-shaped crater.

For decades, geologists surmised the upheaval was an eroded salt dome, theoretically formed by the underlying Paradox Formation. Over eons, this deeply buried and buoyant salt layer squeezed upward in other places throughout the region, warping the surface into dramatic landforms like stone arches and spires.

So, the team of planetary geologists trekked inside the Upheaval Dome crater, where they examined the exposed rock units composing a contorted inner peak. What they found was the famous White Rim sandstone, which should have been buried beneath the crater, was exposed and jumbled together with other well-known rock units. Each unit was highly faulted and turned nearly vertical in places. Something must have forced these underground rocks upward, but was it a violent impact or the gradual flow of salt?

Mysteries of the National Parks: 35 Stories of Baffling Disappearances, Unexplained Phenomena, and More

America's national parks are most known for outstanding beauty and unparalleled adventure―and these natural wonders also hold some of the world's greatest enigmas.

One thing that wasn’t present inside Upheaval Dome was exposed salt from the Paradox Formation. Should rising salt be the culprit, one might expect some to remain, like fingerprints left by the suspect. But looks can be deceiving in geology, and more evidence was necessary. So, Shoemaker and his team searched for other signs of an impact, including shatter cones and shocked quartz. They found a few faint examples of the former, while other researchers eventually found just two grains of the latter.

These discoveries weren’t enough to end the spirited debate, but they did tip the scales toward an impact. Shoemaker might have kept searching, but sadly he died in a car accident a few years later. With the biggest advocate for the impact theory gone, the mystery has lingered for decades. In the meantime, a few things are certain. There is a strange and uniquely contorted crater inside Canyonlands National Park. No one has definitively proved what it is. Upheaval Dome is unlike anything else found on our planet.

Bring this mystery to life by heading to the Island in the Sky District. The popular Overlooks Trail leads about a half-mile to a first lookout and another half-mile to a second viewpoint above Upheaval Dome. More adventurous hikers can descend into the crater on the 8.1-mile Syncline Loop, which is considered the hardest hike in the district due to steep switchbacks and boulder scrambling.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

A Note to our Readers Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.