Scientists Have Never Confirmed a Meteorite From Mercury. Could These Space Rocks From the Desert Be the First?

Two meteorites found in the Sahara show tantalizing similarities to the innermost planet, and while researchers say they are likely not direct samples, “one cannot rule out” the idea

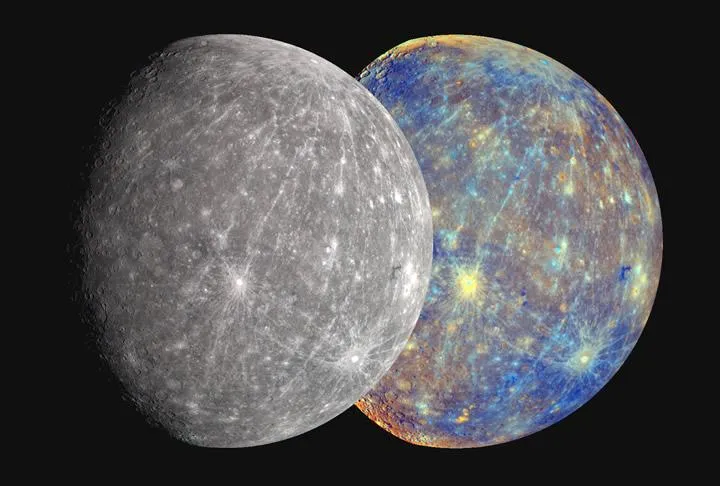

Mercury is a mysterious world. As the closest planet to the sun, it’s a hard-to-reach destination for space missions. So far, only two have made it to Mercury—NASA’s Mariner 10 and MESSENGER spacecrafts.

Accessing debris from Mercury would help scientists study the planet more easily, but that also remains elusive. While more than 1,100 meteorite samples from the moon and Mars have been documented in a database by the Meteoritical Society, there have been no confirmed specimens from the innermost planet.

Now, in a study recently published in the journal Icarus, researchers suggest that two meteorites found in the Sahara Desert in 2023 might be the closest analogs yet to rocks from Mercury—or, though it’s less likely, they could be the first known meteorites from the planet itself.

If their origin is confirmed, the meteorites could help scientists better understand the rocky world’s evolution and formation.

Key question: Why are so many meteorites found in deserts?

Meteorites land more or less evenly across the surface of the Earth—with many falling in the oceans—but they’re more easily found in arid deserts like the Sahara and polar deserts like Antarctica, because there, they stand out from the ground.

In theory, it should be possible for debris from Mercury to reach Earth. “Based on the amount of lunar and Martian meteorites, we should have around ten Mercury meteorites, according to dynamical modeling,” says study lead author Ben Rider-Stokes, a postdoctoral researcher at the Open University in the United Kingdom, to Jacopo Prisco at CNN.

“However, Mercury is a lot closer to the sun, so anything that’s ejected off Mercury also has to escape the sun’s gravity to get to us. It is dynamically possible, just a lot harder,” he adds. “No one has confidently identified a meteorite from Mercury as of yet.”

To determine the Saharan meteorites’ origins, the researchers compared the fragments to observations from the MESSENGER mission, which launched in 2004 and analyzed the components of Mercury’s surface from orbit. Both meteorites share similar mineralogy with what scientists have predicted about the planet’s crust, Rider-Stokes says in a statement. For instance, they contain iron-poor olivine and pyroxene, matching what MESSENGER documented on the planet.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/77/32/7732adbb-1f18-4639-893c-3789508f2d75/1-s20-s0019103525002611-gr1_lrg.jpg)

However, in a piece for the Conversation, Rider-Stokes points out that it’s difficult to definitively link the meteorites to Mercury. For one, scientists have calculated Mercury’s surface to be about four billion years old. The samples are about 528 million years older than that. Additionally, the meteorites both contain only trace amounts of the mineral plagioclase, which is thought to make up over 37 percent of Mercury’s surface.

Sean Solomon, a planetary scientist at Columbia University and former principal investigator for the MESSENGER mission, tells CNN he does not think the meteorites originate from Mercury, because they formed much earlier than the rocks currently on the planet’s surface. Still, he says they hold scientific value, since they share many geochemical characteristics with minerals found on Mercury’s surface—such as very low iron levels and the presence of sulfur-rich minerals.

“These chemical traits have been interpreted to indicate that Mercury formed from precursor materials much more chemically reduced than those that formed Earth and the other inner planets,” adds Solomon, who was not involved with the study. “It may be that remnants of Mercury precursor materials still remain among meteorite parent bodies somewhere in the inner solar system, so the possibility that these two meteorites sample such materials warrants additional study.”

Even though the study authors acknowledge in the paper that it seems unlikely the two meteorites came directly from Mercury, “one cannot rule out a Mercurian origin,” Rider-Stokes says in the statement.

Proving the origins of the meteorites—Mercurian or not—will remain challenging, until a mission brings back direct samples from the planet, he adds in the Conversation. The BepiColombo mission—a joint venture between the European Space Agency and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency that’s currently en route to Mercury’s orbit—could offer high-resolution data about the planet’s composition and history that could help identify the two meteorites’ origins.

Rider-Stokes has taken his research to the annual meeting of the Meteoritical Society in Australia this week. “I’m going to discuss my findings with other academics across the world,” he says to CNN. “At the moment, we can’t definitively prove that these aren’t from Mercury, so until that can be done, I think these samples will remain a major topic of debate across the planetary science community.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sara_-_Headshot_thumbnail.png)