Have Eagle-Eyed Experts Found This 316-Year-Old Stradivarius Violin That Was Looted During World War II?

Eight decades after the 1709 violin known as the “Small Mendelssohn” disappeared, experts think they’ve located it in Japan

In 1945, a rare Stradivarius violin was stolen from a Berlin bank during the chaotic end of World War II. Experts have long assumed that the instrument had been destroyed or lost to history. Now, 80 years later, they think they’ve found it in Japan.

The instrument, created in 1709 by renowned Italian luthier Antonio Stradivari during his “golden period,” was known as the “Small Mendelssohn.” Experts now claim that it’s the same violin as the “Stella,” a Stradivarius dated to 1707. The Stella is currently owned and played by the Japanese violinist Eijin Nimura, who denies the connection.

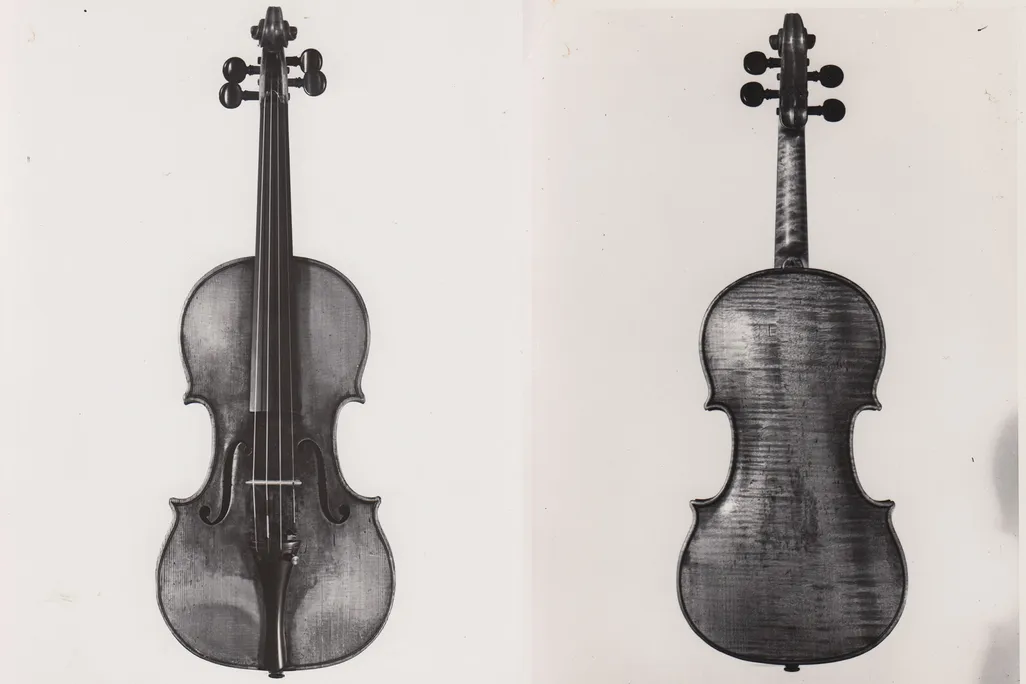

The two instruments were tied together in the summer of 2024 when Carla Shapreau, a cultural property scholar with the Institute of European Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, stumbled upon photos of Stella from a 2018 exhibition in Tokyo. When she noticed the uncanny similarities between the two instruments, her “jaw dropped,” she tells the New York Times’ Javier C. Hernández.

Quick fact: Who was Antonio Stradivari?

Born around 1644, Stradivari was an Italian violin maker who did his best work between roughly 1700 and 1720.

Shapreau heads the Lost Music Project, which searches for cultural objects like instruments and books looted by the Nazis during the war. She has been looking for the Mendelssohn for more than 15 years.

Stradivarius violins, renowned for their superior acoustics and visual beauty, have a certain mystique in the classical world. Stradivari, who lived and worked out of the northern Italian city of Cremona, created more than 1,200 instruments throughout his six-decade career. Some 500 of them, mostly violins, are still in circulation, and they are extremely valuable. In February, a 1714 Stradivarius violin sold for more than $11 million at auction.

The Mendelssohn violin had belonged to the Mendelssohn-Bohnkes, a wealthy German banking family. It was officially registered in the 1930s and photographed at some point before the theft. At this time, Franz von Mendelssohn, a partner at the Mendelssohn Bank in Berlin, hid the violin in the bank’s storage.

In 1938, the Nazis forcibly liquidated the Mendelssohn bank, and its assets, including the family’s Stradivarius, were absorbed by Deutsche Bank. By the spring of 1945, when Hitler died by suicide, the Soviet army entered Berlin and took control of the bank. It’s unclear whether Deutsche Bank was plundered and the violin stolen before or after the Soviets arrived.

For years after the war, the Mendelssohn-Bohnke family tried to find the violin. They placed ads in international magazines and filed a report with Germany’s Federal Ministry of the Interior, but the instrument never resurfaced.

Meanwhile, the violin known as Stella is dated to 1707. Its origins are unclear, but it first appeared in 1995, when it was sold in Paris by an unnamed Russian violinist who claimed to have purchased the instrument in 1953. Shapreau thinks the violin’s label may have been misread or intentionally altered, explaining the 1707 date. The Stella was photographed by string instrument auction house Tarisio in 2000, and Nimura acquired it around 2005.

“It is one and the same violin,” David Rosenthal, the great-grandson of Franz von Mendelssohn, the man who hid the instrument in the Mendelssohn Bank’s storage, tells Le Monde’s Nathaniel Herzberg. “The same dimensions, the same wood grain, dozens of tiny scratches that are exactly identical. Show these photos to any reputable luthier and they will tell you the same.”

Violin experts tell the Times that before 2005, they had never heard of a Stradivarius violin known as the Stella. Still, Nimura has decided against engaging with Shapreau. “We have no information regarding this, including any factual basis that any of your allegations would have any merit,” Nimura’s lawyer, Yoshie Tsuruta, wrote in a recent letter to Shapreau, per the Times.

Jason Price, the founder of Tarisio, estimates that the Mendelssohn is worth around $5 million. However, tracing the provenance of musical instruments that were lost or stolen, especially during the Nazi era, is incredibly difficult. In recent years, many descendants of Jewish families have successfully recovered Nazi-looted artworks, but Shapreau would like to see similar success rates for musical instruments.

“Much has been accomplished regarding the looting of paintings, with many works having been returned to their rightful owners, but much less when it comes to music,” she tells Le Monde.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/asia.png)