Cut Marks on Animal Bones Suggest Neanderthal Groups Had Their Own Unique Culinary Traditions

Neanderthals in two nearby caves used different techniques when butchering animal carcasses in what is now Israel, according to a new paper

Neanderthals living at caves less than 45 miles apart appear to have used different techniques while preparing meat, suggesting the groups may have had their own unique culinary traditions.

In the journal Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology, scientists describe the “distinctive butchering strategies” of Neanderthals living in modern-day Israel. The findings serve as a reminder that “there is no monolithic Neanderthal culture,” says Matt Pope, an archaeologist at University College London who was not involved with the research, to the Guardian’s Nicola Davis.

“The [Neanderthal] population contained multiple groups at different times and places, living in the same landscape, with perhaps quite different ways of life,” Pope adds.

Zooming out even more, the results support the idea that Neanderthals were more intelligent and organized than once thought. Recent research also suggests Neanderthals were running a sophisticated “fat factory” in Germany and that they were capable of hunting and butchering large prehistoric elephants. Neanderthals seem to have cleverly trapped horses near the edge of a prehistoric lake and made hand-crafted wooden spears to hunt them.

“For a long time, Neanderthals were viewed as very practical, focusing on achieving what they needed in the most efficient way,” says lead author Anaëlle Jallon, an archaeologist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, to the Times of Israel’s Rossella Tercatin. “Now we are starting to realize that there were more subtleties, there were cultural aspects.”

Key concept: The surprising complexities of Neanderthal cooking

Research on charred food remains revealed Neanderthals used a wide range of ingredients—including nuts, grasses and other plants alongside meat—and deliberate cooking strategies, like soaking and pounding. They also might have cooked and eaten crab in a cave in modern Portugal.

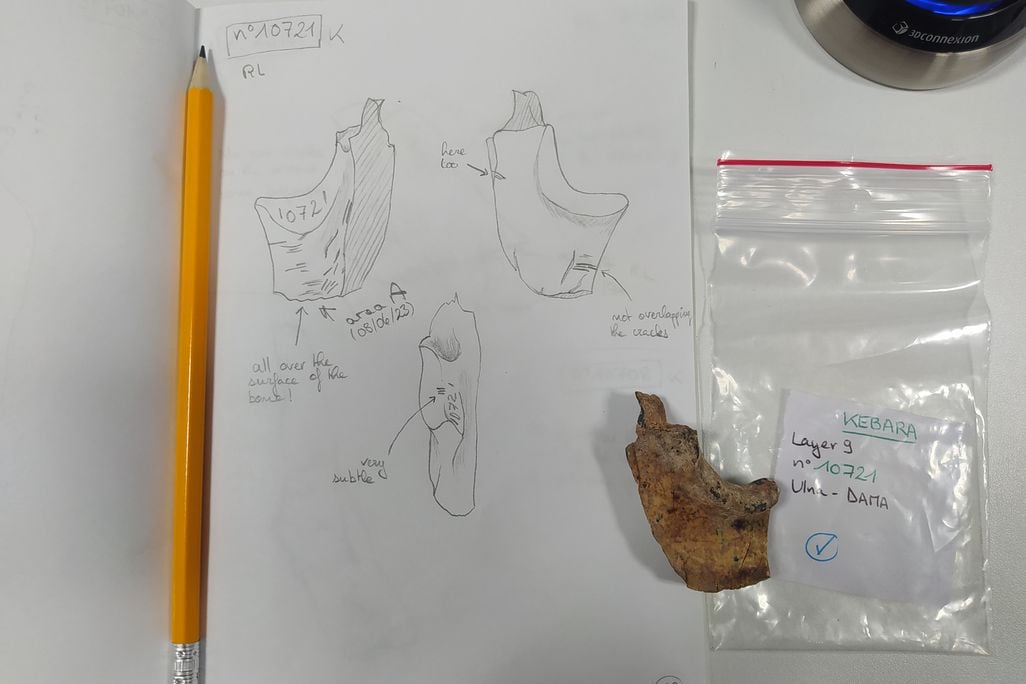

For the new study, researchers analyzed 344 animal bone fragments found at two sites—the Amud cave and the Kebara cave—located in northern Israel. The bones, which were recovered in the 1990s, are between 50,000 and 70,000 years old.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/61/9e/619ed194-92d2-4a42-a912-c0f8795053e2/whatsapp_image_2025-07-10_at_173334.jpeg)

Researchers suggest Neanderthals inhabited both caves at roughly the same time during the Middle Paleolithic period, based on the presence of stone tools, hearths and food remains in each. The two groups were roaming around similar landscapes and hunting the same types of animals—mostly fallow deer and mountain gazelles, but also cow-like aurochs and boar.

But when the scientists took a closer look at cut marks on the bones, they discovered variations that suggest the Neanderthals living at each cave had adopted their own butchery styles, which were likely influenced by social and cultural factors.

“The cuts tend to be more variable in their width and depth in Kebara, and in Amud they are more concentrated in big clusters, and they overlap each other more often,” Jallon tells New Scientist’s Chris Simms. Cut marks at Kebara were more linear, while those at Amud were more likely to be curved.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0c/12/0c1207b4-e722-404a-a0c1-bac2c8bf77a4/amud_6445_10x_cut1_image.jpeg)

Some of the differences could be explained by the type of animal and the specific body part the Neanderthals were butchering. But when researchers investigated the same body parts from the same type of animal—examining the long bones of gazelles from both caves—they found the same variations.

At Kebara, more remains of larger prey were present, and it appeared that the inhabitants butchered the animals in the cave. Neanderthals at Amud, meanwhile, might have done the butchery of these creatures elsewhere. More fragmented and burned materials were recovered from the Amud cave.

It seems the Neanderthals in charge of food prep at each site simply had different methods or preferences, which they may have passed down to their offspring. The evidence appears to support the idea: At the Amud cave, researchers found the same types of cut marks in multiple layers of sediment, which suggests Neanderthals were returning to the site for millennia.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8f/66/8f6658d6-5875-46fc-ab92-b23249ca51f2/fearc-04-1575572-g002.jpg)

“You would expect to find the most efficient way to butcher something to get the most out of it, but apparently, it was more determined by social or cultural factors,” Jallon tells New Scientist. “It could be due to group organization or practices that are learned and transmitted from generation to generation.”

For example, perhaps the individuals living in the Amud cave preferred to dry out their carcasses before processing them, which would have toughened the meat and required different cutting strategies. Or, perhaps different numbers of individuals were involved with the butchery at each site.

“Maybe in Amud, everybody cut themselves a little piece of meat, creating a lot of different cut marks everywhere, while in Kebara there was one person designated to cut everything properly,” Jallon tells IFLScience’s Benjamin Taub.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SarahKuta.png)